- Home

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Caribbean Island Hopping

- Used Sailboats for Sale

Finding Used Sailboats for Sale in the Caribbean

Where would you seek them out, and why would you want to look for a used sailboats for sale all the way down in the Caribbean anyway?

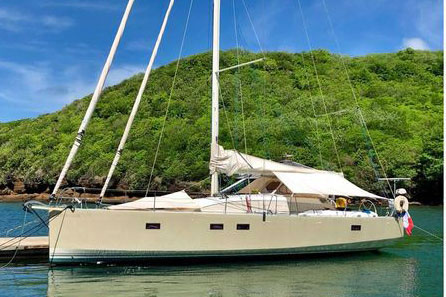

'Sea del Uno', a Beneteau 411

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $83,000

The first part of the question is easy to answer - right here! We're not a broker so we seek no commission, nor do we make a charge for placing the ads. We only allow ads from the owners themselves - or occasionally from their appointed brokers - and yes, it's all for free!

But there are other sources of second-hand cruising yachts in the Caribbean, one of which is the yacht charter companies.

These companies update their fleets from time to time, selling off the older models.

Horizon Yacht Charters have bases on several of the Eastern Caribbean islands, and would be a good place to start looking.

Charter boats are generally optimised to maximise accommodation for fare-paying clients and, whilst being quite acceptable for Caribbean island-hopping, may not make ideal long-distance cruising boats.

'Torvin', a Lagoon 500

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $415,000

Why Should I Buy a Used Sailboat in the Caribbean?

After all, it's a long way to go to look at one, and there's likely to be a lot more to choose from closer to home, but...

- Perhaps you've got time for some extended cruising in the Caribbean but are not very enthusiastic about tackling the long ocean passage necessary to get there, or

- You're looking for a bargain. Sometimes, but not always, the owner of a boat in the Caribbean has had enough sailing and is keen to sell. Maybe he hasn't got the time to sail her back home, or doesn't want to pay someone else to do it for him. That puts you in a strong negotiating position.

- You've been looking for a particular boat for a while now - and here it is!

'Just Now', a Beneteau 463

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $79,500

Getting Her Surveyed

You've found a boat that looks ideal - it's time for a deep and meaningful conversation with the owner, after which you've got a decision to make. Do you...

- Walk away?

- Make an offer subject to survey?

- Go and take a look at her yourself before walking away or making an offer subject to survey?

- Get her surveyed before deciding whether to walk away or take a look at her yourself?

Here's what I would do, assuming I hadn't decided to walk away...

- Ask at least two local professional yacht surveyors to quote for a full survey, and

- Make an assessment of the transport and accommodation costs involved in visiting the boat.

If the cost of (1.) is relatively low compared with the cost of the survey I'd download a copy of Andrew Simpson's 'Secrets of Secondhand Boats' and, armed with this most valuable assistant, go and assess her myself before deciding whether to walk away or appoint a yacht surveyor.

If the cost of (2.) is relatively low compared with the cost of making the trip I'd appoint the yacht surveyor. His report would enable me to decide whether to walk away or, after visiting the vessel, make an offer.

A Selection of Used Sailboats for Sale in the Caribbean

'Heavy Metal', an 11.6m Van de Stadt Cruiser

Location: Curacao, Dutch Antilles

Asking Price: $53,000

'Bijou', a Hylas 46

Location: Panama

Asking Price: $397,500

'Windward', a Tayana 48 DS

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $390,000

'Alkoomi', a Hunter 466

Location: Grenada West Indies

Asking Price: $149,000

'Galileo', a Jaguar 36 catamaran

Location: Grenada West Indies

Asking Price: $150,000 now $120,000

'Coco Rose', a Fountaine Pajot Lipari 41

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $345,000

'Petrel Blue', a Westerly Oceanranger 38

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $38,588

'Wind's Way', a Hardin Seawolf 40

Location: Martinique, French West Indies

Asking Price: $66,000

'BlueJacket', a Freedom 40/40

Location: Belize, Central America

Asking Price: $150,000 $134,900

'Cabo Frio', a Catalina Morgan 43

Location: Grenada, West Indies.

Asking Price: $65,000

'Hitchcock', an RM1260

Location: Grenada, West Indies.

Asking Price: €209,000

'Venture', a Bristol 40

Location: Grenada, West Indies.

Asking Price: $46,000$36,000

'Live the Dash', a Morgan Out Island 37

Location: St Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Asking Price: $36,900$33,900

'Pompoen', a Hans Christian 34

Location: Trinidad, West Indies

Asking Price: $42,000

'Wanuskewin', a Catalina 42 MkII

Location: Lucaya, Grand Bahama

Asking Price: $105,000

'Just Friends', a Hunter 376

Location: Puerto Rico, West Indies

Asking Price: $70,000

'Anna'

'Anna''Anna', a Bavaria 390

Location: Trinidad, West Indies

Asking Price: $35,000 now $28,000

'Untethered Soul', a Vagabond 47

Location: Fajardo, Puerto Rico

Asking Price: $162,000 $96,000

'Freja'

'Freja''Freja', a Voyager 35

Location: Martinique, French West Indies

Asking Price: €35,000

'Golightly'

'Golightly''Golightly', an Island Packet 350

Location: Martinique, French West Indies

Asking Price: $88,000

'Music II', a Morgan 41 Classic

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: $97,500

'Maia', a Moody 376

Location: Martinique, French West Indies

Asking Price: €70,000

'Svea av Valleviken', an Overseas 35

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: €89,000

'Vite & Rêves'

'Vite & Rêves''Vite & Rêves', a Catana 401

Location: Grenada, West Indies

Asking Price: €198,000

Recent Articles

-

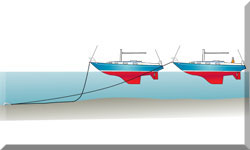

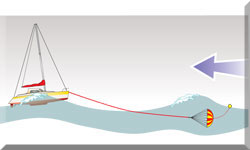

Parachute Sea Anchor Issues: Your Questions Answered

Mar 27, 25 01:52 PM

Parachute sea anchors are vital for stabilizing sailboats in heavy weather, but they can be difficult to deploy. Here we take a look at common issues and their solutions. -

Sailing Drogue Issues: Your Questions Answered

Mar 27, 25 12:52 PM

Stay safe in heavy seas! Learn how sailboat drogues can control speed, prevent pitchpoling, and make storm survival manageable for offshore sailors. -

Solar Panel FAQ's

Mar 27, 25 05:16 AM

Got a question about marine solar panels? You'll probably find the answer here...