- Home

- Sails

Sailboat Sails - The Source of

All Power

If the wind is the fuel, then it's our sailboat sails that are the engine - so they must be carefully designed and accurately constructed if they are to capture the energy of the wind and efficiently convert it to motive power.

All four sails are pulling well on this Bowman 57 staysail ketch

All four sails are pulling well on this Bowman 57 staysail ketchThese days, sail design is carried out by professional designers using dedicated computerr software to produce both the overall three-dimensional curvature, and the shape of the individual flat panels that go to make up the whole sail.

It remains for the sailmaker to use his skill and expertise to sew the parts of the sail together into a robust sail that takes up the desired shape when filled with wind.

Whilst Dacron sail cloth is still the most popular choice for cruising sailboat sails, skippers requiring higher performance racing sails in pursuit of fame and glory must be prepared to pay handsomely for increasingly sophisticated woven fabrics such as Kevlar and Twaron for example - and considerably more for laminate and moulded sailboat sails.

But before we get on to the more interesting stuff, less start with the basics...

Parts of a Sail

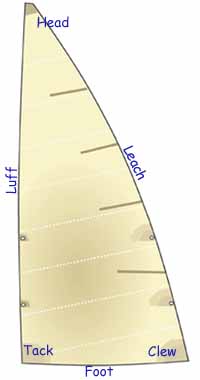

Sides and corners of a triangular sail

Sides and corners of a triangular sailThe Head: The point at which the halyard is attached

The Tack: This is attached to the gooseneck if it's a mainsail, the furling drum (usually) if it's a foresail and the tack line if it's a spinnaker.

The Clew: The point at which the sheet is attached

The Luff: The leading edge of the sail.

The Foot: The lower edge of the sail

The Leach: The trailing edge of the sail

As sailboat sails are modified triangles in shape, with one or more edges curved, calculating sail areas is fairly straightforward.

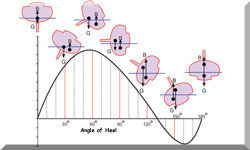

Lift and Drag

For windward work, sailboat sails must provide lift. This is generated through high-speed, low-pressure air on the convex side of the sail and low-speed, high-pressure air on the other.

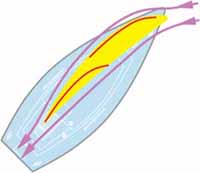

Airflow over the sails when close-hauled

Airflow over the sails when close-hauledWhen sailing hard on the wind, the headsail and the mainsail work together as a single foil.

Drag - both aerodynamic and frictional - opposing forward momentum, is an unwelcome but inevitable associate. An efficient windward sail must be cut to maximise lift and minimise drag.

But as we sail further off the wind and trim the sails accordingly, drag and lift become less important. Sailing dead downwind with the wing-and-wing set up illustrated below, it's the drag that propels us - and there's no lift to windward.

Light Weather and Downwind Sailboat Sails

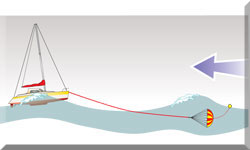

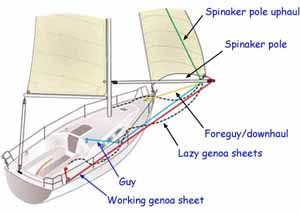

and there should be a preventer on the main...

and there should be a preventer on the main...In a following breeze, the large stable area of a 'wing and wing' set-up provides reasonable performance.

But with the jib poled out and the mainsail secured against an accidental gybe by a preventer, you'd be ill-advised to be crossing shipping lanes with this sail configuration.

Sloops perform well under this rig, but cutter rigged sailboats much less so, penalized as they are by the relatively small area of the yankee and the now redundant staysail.

Lightweight Headsails

Sometimes called multi-purpose genoas, these types of sails are designed for windward sailing in light conditions when the working headsail is too small or heavy to produce much drive.

They are set flying, so there's no need to remove the furled headsail and as long as they're set inside it, can be tacked in the normal way.

These radially cut nylon sails are intended for apparent wind speeds up to 12 knots and perform well in the range between close-hauled and a beam reach.

Often incorporating a HMPE (high-modulus polyethylene) luff to enable it to be properly tensioned, they can be used with a lightweight furler. In light winds, and particularly if sailing downwind, many sailors furl the headsail and reach for the ignition keys.

Other skippers may still furl the headsail - but hoist a cruising chute or spinnaker in its place.

Roller Furling Sails

Few cruising sailors choose to use hanked-on headsails these days, other than perhaps for the staysail on a cutter-rigged sailboat.

In fact, I believe that having a furling gear on a staysail is a missed opportunity, as you've lost the ability of hoisting a hanked-on storm jib when conditions demand it.

Roller furling genoas are rightly very popular, as the alternative is a sail locker stuffed with a number of different sized jibs - and I certainly don't miss wrestling with an uncooperative headsail on a pitching deck in a rising wind.

But I've little enthusiasm for roller furling mainsails as they don't share the simplicity and reliability of furling headsails, contained as they are within either the boom or the mast. I'll stick with slab (or jiffy) reefing and lazy jacks for mainsails, thank you.

However, there are plenty of experienced offshore sailors that would disagree with me. Take look at what Brian Mistrot has to say about them...

Cross-cut and Radial Sails

Until computers enabled us to properly understand the stress patterns in sails and the distortion characteristics of the fabrics, sails were fabricated in cross-cut fashion using weft-orientated fabric.

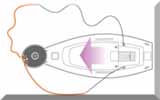

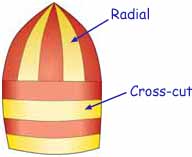

Radial and crosscut sections on a radial head spinnaker

Radial and crosscut sections on a radial head spinnakerAlthough radially cut sailboat sails are known to hold their shape better than cross-cuts, smaller sails, where the gain would be minimal, are still usually cross-cut. As size increases the improved directional stability of a radial sail becomes increasingly desirable.

The radial head spinnaker shown here is a good example of both techniques.

There’s considerably more fabric wastage in the fabrication of a radially cut sail and a lot more stitching involved, so it’ll come as no surprise then that they’re more expensive than cross-cuts.

Further Reading...

Recent Articles

-

Is Marine SSB Still Used?

Apr 15, 25 02:05 PM

You'll find the answer to this and other marine SSB-related questions right here... -

Is An SSB Marine Radio Installation Worth Having on Your Sailboat?

Apr 14, 25 02:31 PM

SSB marine radio is expensive to buy and install, but remains the bluewater sailors' favourite means of long-range communication, and here's why -

Correct VHF Radio Procedure: Your Questions Answered

Apr 14, 25 08:37 AM

Got a question about correct VHF radio procedure? Odds are you'll find your answer here...