- Home

- Electronics & Instrumentation

Integrating Your Boat Electronics and Instrument Systems

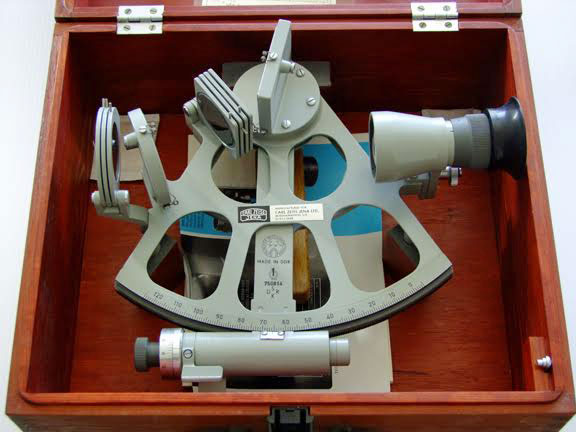

When I first ventured offshore, boat electronics were delightfully basic. Navigation felt like a blend of art and alchemy, relying on sextants, radio direction-finding (RDF) equipment, and position lines to conjure up our place on the water. The tools of the trade—like the trusty Walker towed log—were essential companions, but times have certainly changed.

My sextant hasn't been out of its box for years

My sextant hasn't been out of its box for yearsToday, my RDF set is likely gathering dust in a museum, and the sextant, though still onboard for nostalgia (and emergencies), rarely sees daylight.

A magnetic compass was once the pinnacle of cockpit technology, paired with stand-alone instruments like a speed log, a depth sounder, and a wind indicator perched atop the mast. Back then, that was the height of sophistication.

and neither has my Walker log

and neither has my Walker logNow? We've stepped into an era of integrated electronics that transform how we navigate, connect, and sail.

The Evolution of Integrated Boat Electronics

There's no reason why you can't stick with a 'stand-alone' system of instrument systems if you prefer, but many of us go for the added benefits of integrated boat electronics where the wizardry of the marine manufacturers enable each of the instruments to 'talk' to the others.

The downside of an integrated instrument system is that if one unit fails, it may compromise the performance of another.

A typical boat's integrated electronic instrumentation system

A typical boat's integrated electronic instrumentation systemA typical basic integrated electronic instrument system for offshore cruising is shown above, the primary components being:

- Depth instrument, receiving its input from a thru-hull transducer;

- Speed instrument, receiving its input from a thru-hull paddlewheel log unit;

- Wind instrument, receiving its input from a masthead anemometer;

- GPS unit, or a Chartplotter;

- Heading sensor, essentially a gyro-controlled fluxgate compass which may or may not have a display unit;

Features of an Integrated Electronic System

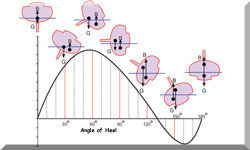

Whilst each of the instruments in an integrated system can function individually, it's only when the sailboat instruments conspire together that additional functionality can be properly gained. For instance:

- The wind instrument can 'talk' to the speed unit and 'velocity made good to windward' can be displayed;

- True (rather than apparent) wind speed and angle off the bow can be displayed;

- With further data from the heading sensor, the heading on the opposite tack can be computed;

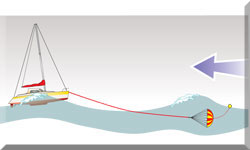

- The autopilot, guided by GPS routes, adjusts for tidal drift, offering precision steering that once seemed like science fiction.

What's New in Marine Technology

Today's systems are pushing the boundaries of what's possible. Advanced units like the Simrad NSO evo2 or B&G Zeus T7 Touch showcase dual processors for seamless multitasking—imagine plotting a course and running radar simultaneously without lag. The Zeus T7 even introduces "Sail Time" calculations, factoring in tacking angles and dynamic tides for pinpoint predictions.

And that’s not all. Wi-Fi-enabled systems allow you to control navigation, engine diagnostics, and even entertainment systems from your smartphone. Meanwhile, solar-powered devices are becoming a must-have for eco-conscious sailors, offering sustainability and reduced energy costs. These innovations show how technology is making life at sea not only easier but greener.

Safety and Advanced Features

Modern radar systems enhance safety with millimeter-wave technology, providing crisp, high-resolution imaging in the most challenging conditions. Pair this with real-time weather monitoring to stay ahead of storms or tidal changes, and you’ve got a system that truly has your back.

AIS-enabled VHF radios now integrate seamlessly with chartplotters, bringing critical collision avoidance data to your fingertips. And let's not forget the other lifesaving technologies within the GMDSS framework: EPIRBs, satellite communications, and search-and-rescue transponders. With these tools onboard, you'll navigate with confidence, knowing you're well-prepared for any situation.

A Few Words of Caution

Integration has its pitfalls. A malfunction in one system can ripple through the network, potentially affecting others. Regular maintenance is key—clean components to ward off saltwater corrosion, and keep firmware updated to avoid compatibility issues.

And let’s not overlook the troublemakers of the sea: crustaceans. They have an uncanny fondness for log impellers, disrupting speed readings and leading to inaccurate data across the system. Addressing this promptly, even if it means temporarily removing the thru-hull unit, can save you a world of frustration.

The Practical Side: Costs and Upgrades

From budget GPS units at £150 to high-end integrated setups exceeding £8,000, the cost spectrum is vast. Phased upgrades can be a great option if you're not ready for a full overhaul—just ensure compatibility to avoid future headaches. For those prioritizing safety, investing in radar and AIS functionality should be top of your list.

Recent Articles

-

Albin Ballad Sailboat: Specs, Design, & Sailing Characteristics

Jul 09, 25 05:03 PM

Explore the Albin Ballad 30: detailed specs, design, sailing characteristics, and why this Swedish classic is a popular cruiser-racer. -

The Hinckley 48 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:44 PM

Sailing characteristics & performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley 48 sailboat... -

The Hinckley Souwester 42 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:05 PM

Sailing characteristics and performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley Souwester 42 sailboat...