- Home

- Anchoring Skills

How to Anchor a Boat

A Vital Skill for All Cruising Sailors

It's no surprise that knowing how to anchor a boat securely is one of the most hotly discussed topics when a group of cruising sailors get together. After all, if we sailboat skippers are to sleep soundly at night, we need to be confident that our sailboat is properly anchored - and when later left unattended with all the crew ashore, will still be where we left it upon our return.

So, boat anchoring isn't something to be taken lightly.

As a general rule, ground tackle should be as heavy as the crew can reasonably manage, and if it's to do as intended - properly deployed.

Incidentally, if you use a 35lb anchor, 8mm chain, and never anchor in more than 30 feet of water and are reasonably sound in body and mind, then you can probably manage with a manual windlass.

But if any of those conditions are exceeded, you'll really appreciate an electric one. But choose one with a manual back-up - just in case.

Weather and Environmental Considerations

Before you even think about dropping anchor, it's crucial to assess the weather and environmental conditions that could affect your anchoring.

Weather Forecasting

Always check the weather forecast before setting anchor. Sudden changes in wind speed and direction can impact your boat's position and the holding power of your anchor. Utilize reliable weather apps, marine radios, or onboard instruments to stay informed about:

- Wind Conditions: Know the current wind speed and forecasted changes. Strong winds require a more secure anchoring setup.

- Storm Warnings: Be aware of any approaching storms or squalls that could necessitate additional precautions or a different anchorage altogether.

Tidal Influences

Understanding tides and currents is essential:

- Tidal Range: Know the difference between high and low tide levels to ensure adequate water depth throughout your stay.

- Currents: Be aware of how currents might shift your boat, affecting the anchor's holding power and your swing radius.

Dropping the Anchor

First find a suitable spot, acceptable depth and seabed type, and clear of any other anchored boats, then:

- Stop the boat over it and drop the anchor, being careful not to drop a load of chain on top of it;

- Let the boat drift back gradually paying out chain without disturbing the anchor;

- When you've let out sufficient scope (see below), secure the anchor chain on deck;

- Now leave it for a few minutes while the anchor digs in and takes its initial set;

- Now motor slowly astern until the chain straightens out;

- Watch the chain carefully as you increase engine revs to spot any signs of the chain jumping, indicating a dragging anchor;

- All seems OK? Then take a transit before increasing engine revs further;

- Dragging? Yes? Then weigh anchor and start the whole process again;

- OK now? Yes? Then hook up the snubber and let out more chain until there's a loop of it between the snubber hook and the bow roller;

That's it, you're in - you know how to anchor a boat. Award yourself a beer!

Scope and Swing Radius Calculation

Calculating the correct scope and understanding your swing radius are fundamental to secure anchoring.

Calculating Scope

Scope is the ratio of the length of the anchor rode to the vertical distance from the bow to the seabed.

- Calm Conditions: A minimum of 4:1 scope (e.g., 30 feet of rode for 10 feet of water depth).

- Moderate Conditions: Increase to 5:1 scope.

- Heavy Weather: A 10:1 scope provides added security.

- Adjusting for Bow Height: Include the distance from the waterline to the bow roller in your calculations.

Note that these are the recommendations for an all-chain rode. The scope should be increased for rope/chain rodes.

Swing Radius Awareness

Your boat will swing in a circle around the anchor as wind and current change.

Calculating Swing Circle:

- Swing Radius = Length of rode + boat length.

- Ensure this circle doesn't overlap with other boats or hazards.

Monitoring Space:

- Be mindful of the anchoring configurations of nearby vessels (all-chain vs. rope rode) as swing patterns can differ.

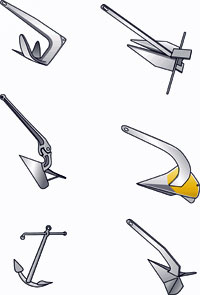

Choice of Anchor

Most cruising sailboats are equipped (or should be) with at least two types of anchors (each with their own separate rodes), a plough or spade type being the preferred choice for the bower, and possibly a lightweight Danforth type as a kedge.

Different anchors perform better in varying seabed conditions:

- Plow (CQR) Anchors: Excellent in sandy or muddy bottoms, known for their ability to reset if the wind or current changes.

- Spade Anchors: Provide reliable holding power in diverse seabeds, including sand, mud, and gravel.

- Bruce (Claw) Anchors: Ideal for rocky and sandy bottoms; they set quickly and have good holding power.

- Danforth Anchors: Lightweight and work well in sand or soft mud but may struggle in grassy or rocky areas.

- Fisherman Anchors: Effective in heavy grass, weeds, or rocky bottoms where other anchors might fail.

In spite of its awkwardness, it's no bad thing to have a disassembled fisherman anchor stowed wherever you can find space for it.

Modern plough and spade type anchors are designed to bury themselves completely. For this to happen, the burying force applied by the chain must be horizontal. Increasing the horizontal force to the point that the anchor drags, it will do so by ploughing along below the seabed.

This is not good; as sooner or later it will meet a change in seabed conditions and break out. With anchors of the same type, the larger versions will always require a progressively greater horizontal force before they start to drag.

But some anchor designs consistently perform much better than others, as this boat anchoring test report confirms.

Anchor Size Recommendations

Selecting the correct anchor size depends on your boat's specifications:

- Boat Length and Displacement: Manufacturers provide guidelines based on these factors.

- Sailing Conditions: If you frequently anchor in challenging conditions, consider an anchor one size larger for added security.

- Redundancy: Carry at least two types of anchors to handle different seabed conditions and emergency situations.

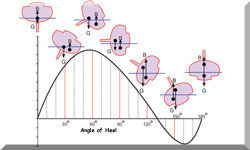

The Critical Angle

So for the anchor to work as it should, the pull on it must be horizontal, ie the end of the chain must remain laying flat on the seabed. But if we haven't deployed enough of it, it won't be.

As we all know, to weigh anchor we shorten the scope thereby increasing the angle of the rode at the anchor to the point at which it rotates and breaks free, enabling us to haul it aboard.

For most types of small boat anchors this angle has been found to be around 15° to 20°. So when we want the anchor to stay put, we need to be sure that this critical angle isn't reached.

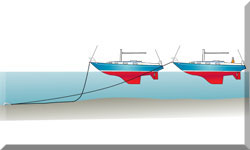

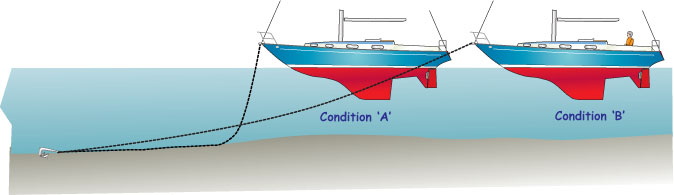

Which condition would you feel most secure in?

Which condition would you feel most secure in?Artwork by Andrew Simpson

Take a look the above sketch, which shows a sail boat anchored in 10m of water. All is well with the chain slack (Condition 'A'), but when the wind picks up and the sailboat moves aft the chain is tight with no catenary and the end of the chain just clear of the seabed (Condition 'B'). If the critical angle has been exceeded you can expect to drag.

To avoid this unhappy situation, some basic trigonometry tells us that the minimum scope/depth ratio to should be 4:1, not 3:1 as is often quoted for an all-chain rode.

Remember that this is the length of the submerged rode; if you're measuring scope at the bow roller add 5 feet (1.5m) or so (the height of the stemhead above the waterline) to the actual depth before applying the 4:1 rule - or make it 5:1 to be on the safe side.

Read more about deploying a realistic length of anchor chain...

Chain or Rope?

The bar-taut rode shown is clearly undesirable, but it's a lot more readily achieved with an all-rope rode than an all-chain one.

Chain, having a much higher density than rope, falls naturally into a gravity-assisted catenary from the bow roller, which resists the tendency to straighten out.

This serves two functions; it applies a force in the chain opposing the wind-load on the boat, and it absorbs energy when the boat surges back in gusts. Of course a 10mm chain will apply more opposing force and absorb more energy than an 8mm one. Once again, big is best.

But let's go back to the bar-taut situation for a moment. Here the chain has lost its energy-absorbing catenary, so any further load from a gust or a wave striking the bow will be applied directly to the anchor.

Such shock loads can be enormous, and are almost bound to cause the anchor to drag and ultimately break out. But in the same situation an all-rope rode will absorb such shock loads due to its lower modulus of elasticity - it stretches more.

But that's not to say an all-rope road is better than chain. It isn't; the required scope to avoid the bar-taut situation will be much more than for chain - and one nick from a piece of coral on the seabed and its game-over.

So definitely not an all-rope rode, but a chain to rope rode can make a lot of sense.

How to Anchor a Boat with an All-Chain Rode

With no wind, current or waves the anchor chain will hang vertically from the bow roller.

As the wind picks up, the yacht will drift back lifting as it does so just enough chain from the seabed for the catenary force to balance the load applied by the wind.

As the wind increases further, more chain will be lifted until the point is reached where only a few links remain on the seabed.

This is the boundary condition, and is the limit for safe anchoring with an all-chain rode; any further increase in tension and the chain will start to snatch at the anchor - with predictable results.

The solution of course is to let out more chain - but how much? Well that depends on a number of factors, ie:

- How hard you expect the wind to blow;

- The depth of water you're anchored in;

- How heavy your chain is;

- How big your boat is;

- How much chain you've got.

But conventional wisdom for sail boat anchoring has it that a 10:1 is the maximum practical scope/depth ratio, after which the rule of diminishing return applies.

So on that basis a 30 feet (10m) depth of water might suggest to you that you need to carry 300 feet (100m) of chain. That's going to be mighty heavy, and stowed exactly where you don't want it - right in the bow.

But there is a way of reducing this weight without reducing the length of chain or its strength. Intrigued? Then read about Proof Coil, High Test and BBB Anchor Chain...

How to Anchor a Boat with Chain-to-Rope Rode

Let's assume that wherever you can, you anchor in less than 30 feet (10m) of water.

The 5:1 rule says you need to deploy 150 feet (50m) of chain in moderate winds. A good compromise is to have this length of chain attached to around 100m of nylon rode, either 3 strand or, better still, 8 plait anchor rode.

Either type splices neatly into the chain links, with little if any loss of strength, but the spliced part may require some help over the anchor windlass.

Most of the time you'll be anchored on an all-chain road, but when you need more scope you'll have lots of nice stretchy nylon rode to absorb the shock-loads.

A tip - have a few feet of chain attached at the inboard end on the rope. If, in extreme conditions, you ever have to deploy it all, you'll have chain going over the bow roller where chafe would otherwise be a major risk.

You'll not be short of other things to worry about!

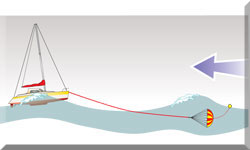

The Essential Snubber Line

If you've got all chain between your anchor and your bow roller, you need a snubber to absorb the shock loads caused by sudden gusts in the wind.

The snubber line absorbs snatch loads on the chain

The snubber line absorbs snatch loads on the chainThe best material for a snubber is 14mm to 20mm diameter nylon rope - 3 strand is fine, but better still is the 8 multi-plait nylon rope we spoke about earlier.

For it to work properly as a spring it needs to be at least 30 feet to 40 feet long, attached to the chain with either a rolling hitch or a chain hook, with the other end secured to a strong point on deck.

It won't reduce the ultimate load on the anchor, but it will greatly reduce the severity of the snatching.

More about snubbing the anchor...

Conclusion

Anchoring is both an art and a science, blending technical knowledge with practical experience. By considering weather and environmental factors, selecting the appropriate anchor, mastering deployment techniques, and practicing good etiquette and safety measures, you ensure not only the security of your vessel but also contribute positively to the boating community. Equip yourself with knowledge, stay vigilant, and you’ll anchor with confidence wherever your adventures take you.

Next: How to join anchor chain...

Recent Articles

-

Small Boat Radar Systems: Your Questions Answered

Apr 13, 25 06:40 AM

Whatever your question about small boat radar systems, you're very likely to find the answers here... -

How a Marine EPIRB Can Get You into Trouble, As Well As Out Of It

Apr 12, 25 05:51 PM

Activating a marine EPIRB or a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) when you're not in distress can get you in big trouble with the Coastguard, as this cautionary tale relates. -

What is an EPIRB?

Apr 12, 25 05:43 PM

Got any EPIRB-related questions? You're almost certain to find the answers here...