- Home

- Bluewater Sailing

- Sailboat Galley Layout

- Marine Water Heating Systems

Getting Hot Water on Your Boat: A Guide to Marine Water Heating Systems

Key Takeaways

Marine Water Heating Systems are essential for comfort aboard. The most efficient and cost-effective method for an offshore sailor with a freshwater-cooled engine is the calorifier (or boat water heater). This insulated heat exchanger uses the engine's waste heat to warm your domestic water supply for free while underway, effectively turning a by-product of combustion into a valuable commodity. Combining this with an AC immersion heater gives you versatile hot water, whether you're at sea or tied up to shore power. Crucially, offshore systems demand smart energy management and redundancy planning for longevity and self-sufficiency.

Table of Contents

The Ingenuity of the Marine Calorifier

Any boat engine that runs regularly is producing heat, and if you've got a freshwater-cooled engine, you really should be taking advantage of that. The combustion process creates waste heat, and once you’ve shelled out for the equipment, you can genuinely get something for nothing: free hot water.

That clever piece of kit is known as a marine calorifier, or simply a boat water heater.

In essence, a calorifier is just a highly insulated storage tank with a coil of pipe—a heat exchanger—running right through it. This coil is plumbed directly into your engine’s closed cooling circuit. Hot coolant flows from the engine through the coil, transferring its heat to the fresh water held in the surrounding tank, which is then ready for your domestic use.

This system is generally retro-fitted without too much difficulty, provided your vessel meets two key prerequisites:

- A Freshwater-Cooled Engine: Unlike a raw seawater-cooled engine, this type of marine engine has a separate, closed system with its own header tank, which is then cooled via a freshwater/seawater heat exchanger. This is the circuit we tap into.

- A Pressurised Domestic Water System: A simple manually pumped system, laudable though it is for saving power, just won't do the job here. Thankfully, converting to a pressurised system is usually a straightforward affair for most modern boats.

Material Selection & Longevity

The tank material is critical for avoiding early failure in a vibrating, corrosive environment. Marine calorifiers are almost universally made from high-grade stainless steel, typically 316L. This material offers superior resistance to corrosion from chlorinated municipal water and galvanic action. Never use domestic, glass-lined tanks; they're designed for static installation and the enamel will quickly crack under the constant movement and vibration of an offshore yacht.

How a Calorifier System Works

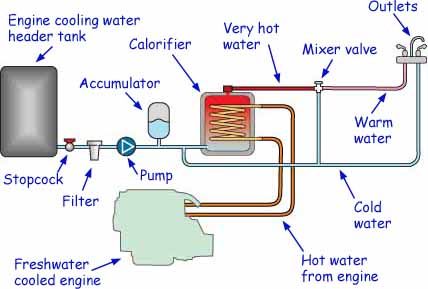

The diagram below shows a typical hot and cold water installation. It often incorporates both a pressure pump and an accumulator tank.

- Pressure Pump & Accumulator: Most pressure pumps maintain steady flow by cycling on and off. The accumulator tank—containing water and air, sometimes separated by a diaphragm—absorbs this pulsation and ensures a steady, non-pulsed delivery at the tap. However, some newer microprocessor-controlled variable-speed pumps eliminate cycling, which makes the accumulator tank redundant.

- Mixer Valve (Thermostatic Blending Valve): This is a critical component for safety and conservation. It operates thermostatically, introducing a metered amount of cold water into the hot water flow as it leaves the calorifier. This maintains a regulated, safer temperature at the tap and conserves the hot water stored in the tank by preventing it from being used at its full, scalding temperature.

- Installation Tip for Efficiency: The pipework connecting the calorifier to the engine should be as short as possible to minimise heat loss. Crucially, the calorifier should be installed lower than the level of the engine’s header tank to ensure proper circulation and bleed-off of any trapped air.

Calorifiers are well insulated and can keep water warm for a couple of hours after the engine has been turned off. But, if you haven’t run the engine for a much longer period, you know that turning on the hot tap won't produce the desired result.

Calorifier Sizing & Placement: Practical Considerations

It won't come as a surprise to you that space and weight distribution are always at a premium on a boat. Choosing the right size and location for your calorifier is a crucial part of the process.

Sizing Guide

Sizing isn't a science, but a good rule of thumb for cruising yachts is to aim for a unit that gives you adequate hot water without adding excessive weight or taking up too much prime storage space.

Sizing Guide

| Crew Size | Volume (Litres) | Usage Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 15–20 | Essential washing up & short showers |

| 2–4 | 25–40 | Comfortable, regular showering |

| 4+ | 40+ | Extended cruising & higher demand |

Strategic Placement

For optimum performance and safety, keep the following in mind:

- Proximity to Engine: As mentioned, the closer the calorifier is to the engine, the less heat is lost in the plumbing lines, ensuring quicker heat-up times and hotter water.

- Accessibility: Choose a spot that allows easy access for plumbing connections, electrical wiring (if an immersion heater is included), and, most importantly, for maintenance tasks such as draining for winterisation.

- Structural Support: A 40-litre calorifier full of water weighs approximately 40kg. That’s a significant, concentrated load. Ensure the mounting area—often under a bunk, in a locker, or in the engine space—is structurally robust enough to handle the weight, especially when the boat is heeled or pounding in a heavy sea.

The reliable delivery of hot water is an integral part of making a sailboat's living space truly functional, especially in the most used areas. When planning any major plumbing or appliance installation, it’s worth reviewing your whole workspace to ensure maximum efficiency—you can find more advice and considerations in our guide to Choosing the Best Sailboat Galley Layout.

Advanced Energy Management & Off-Grid Use

Offshore sailors need to heat water without running the engine continuously. This is where dual-coil systems and careful power calculations come into play.

Dual-Coil Heating Sources

If you opt for a calorifier with a twin coil, you gain crucial heating redundancy:

- Engine: Primary source, offering free hot water underway.

- Alternative Heater: The second coil can be plumbed into a dedicated liquid-fuelled central heating system (like a diesel heater) or a boiler stove. This allows you to generate hot water independently using minimal fuel, regardless of whether the engine has been run for days. This is a common setup on yachts cruising in higher latitudes.

Running the Immersion Heater Off-Grid

Electric immersion heaters are fantastic when plugged into shore power, but they are a heavy load for battery-based systems:

- The Power Cost: A typical 1.0kW immersion element will draw around 4.3A at 230V AC. However, if you run this through an inverter from a 12V battery bank, the draw is closer to 80 to 90A, plus inverter losses.

- Practicality: Running an immersion heater offshore should only be considered if you have a large battery bank and are simultaneously charging it heavily, such as via high-output alternators, large solar arrays, or running a dedicated AC generator. Otherwise, you'll deplete your batteries alarmingly fast for what is ultimately a comfort item. It's often far more power-efficient to just run the main engine for 45 minutes.

Electric Immersion Heaters: Shore Power & Generators

Electric immersion heaters are a fantastic backup and primary source of heat when you're not running the engine. They're much like the smaller versions of the heaters we’re accustomed to at home.

These heaters require AC power. This means their use is restricted to when you're alongside and hooked up to an onshore supply, or if you have an AC generator running aboard. For most cruising sailors, this versatility is key.

- Integration: Immersion heaters are very often combined with a calorifier in a single unit. Reputable stainless steel units, like those from Isotherm, are designed this way and come equipped with their own thermostat.

- Power Draw: In immersion heater mode, these units typically draw around 6.5A at 120V or a lower amperage at 230V, depending on the heating element's wattage. It’s important to know the power consumption, as it can be a heavy load on smaller generators or older shore power hook-ups.

Alternative Heating Methods

While the calorifier/immersion combination is the gold standard for cruising yachts, other methods are available, though they come with distinct drawbacks.

Hot Water from the Sun!

Intended for campers, but they’re perfect for sailors cruising in warm, sunny climes. Simple, cheap, and effective, these black plastic bags absorb solar radiation and can heat water quite quickly. I’d suggest every cruising sailor should have a couple of these on board for quick, off-grid rinsing on deck. They’re a great, low-tech solution.

Gas Water Heaters

A bulkhead-mounted gas water heater is simply not popular on sailboats anymore. Many experienced skippers believe they’re just too plain dangerous due to the risks associated with an open flame and gas leaks in a confined marine environment.

I used to have one on my previous boat, the Nicholson 32 Jalingo, and lived to tell the tale. But would I have another? No, definitely not.

My advice, based on years of offshore experience, is simple: don’t touch them. If you’ve got one, get it decommissioned & get rid of it. If you absolutely insist on buying one, make absolutely sure it has an automatic low gas pressure cut-off switch and a flame failure device fitted, and that it’s properly serviced & regularly maintained by a professional. The risk simply isn't worth the convenience.

Maintenance, Winterisation & Troubleshooting

A well-maintained marine water heating system will provide years of reliable service.

Routine Maintenance

- Anode Check: If your calorifier features an anode (usually an optional extra on marine units, but worth checking), inspect and replace it annually, especially if you use the immersion heater frequently.

- Pressure Relief Valve: Check the pressure relief valve periodically to ensure it hasn’t seized. This is a critical safety component designed to prevent the tank from rupturing if pressure builds up due to overheating or a fault in the system.

- Blending Valve Check: Ensure the thermostatic mixing valve is functioning correctly. If the hot water temperature becomes erratic, this valve may need flushing or replacement.

Troubleshooting & Redundancy

Offshore preparation means knowing how to handle component failure:

- Pump Cycling: If your pump cycles on & off rapidly when no tap is open, it usually means the accumulator tank has lost its air charge and needs re-pressurising, or there is a very small leak somewhere in the system.

- Emergency Hot Water Bypass: If the calorifier develops a leak (often identifiable by water in the bilge near the unit), you need a quick fix. Install bypass valves during the initial fit-out to quickly isolate the calorifier and restore cold water pressure to the rest of the boat until you can get to a repair facility. This is essential for maintaining basic plumbing function.

Winterisation Procedure

For those of us in colder climes, winterisation is essetial to prevent freezing and damage.

- Isolate & Drain: Isolate the water system by turning off the pump and closing all inlet valves. Open all hot and cold taps to release system pressure.

- Empty the Tank: The calorifier itself must be completely drained. This usually involves locating the drain plug or removing a hose connection at the lowest point of the tank. Simply turning on the taps won't empty the calorifier's main body.

- Bypass: If you plan to introduce non-toxic, food-grade antifreeze into your domestic water system, you must bypass the calorifier first. Antifreeze should not be run through the heating element or the tank itself. You can install a bypass loop with valves to isolate the unit easily.

- Reconnect: Once the boat is de-winterised in the spring, flush the system thoroughly before use.

Summing Up

Installing a calorifier as the centrepiece of your Marine Water Heating Systems is one of the best upgrades you can make to your cruising boat. It’s a simple, reliable, and fundamentally clever way to harness the energy you're already spending to power your boat. It enhances comfort, supports hygiene, and truly turns a boat into a home at sea. For the experienced sailor, this combination of free, engine-generated hot water, shore power backup, and planned redundancy is an investment that pays dividends in comfort every time you turn the key.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for a calorifier to heat water?

How long does it take for a calorifier to heat water?

Typically, a well-sized calorifier connected to a fully warmed engine will heat the entire tank to operational temperature within 30 to 60 minutes of the engine running at cruising RPM.

Do marine calorifiers require an electrical connection?

Do marine calorifiers require an electrical connection?

A calorifier only requires an electrical connection if it includes a built-in AC immersion heater. If it relies solely on the engine's heat exchanger, it requires no 12V or 230V power for heating, only for the water pressure pump to supply the unit.

What is the safe temperature for the water leaving the taps?

What is the safe temperature for the water leaving the taps?

While the water inside the calorifier can reach temperatures above 70oC (around 160oC), the thermostatic blending valve should be set to supply water at the tap at a safe, usable temperature, typically between 45oC and 50oC (113oF and 122oF) to prevent scalding.

Can I connect my calorifier to a heating stove or diesel heater?

Can I connect my calorifier to a heating stove or diesel heater?

Yes, many modern calorifiers are designed with twin coils, allowing one coil to connect to the engine's cooling circuit and the second coil to connect to an alternative heat source, such as a diesel-fired central heating system or a solid fuel stove with a water jacket. This provides truly flexible year-round hot water.

What is the typical lifespan of a marine calorifier?

What is the typical lifespan of a marine calorifier?

A high-quality, stainless steel marine calorifier can easily last 15 to 20 years or more with proper care, especially if the pressure relief valve is checked regularly and the unit is correctly winterised each year to prevent corrosion from freezing damage.

Why shouldn't I use a domestic water heater on a boat?

Why shouldn't I use a domestic water heater on a boat?

Domestic water heaters are typically glass-lined, which is fragile. The constant vibration and motion of a boat, especially in heavy weather, will quickly cause the glass lining to fail, leading to internal corrosion and premature tank failure. Only marine-grade stainless steel units should be used.

Recent Articles

-

Allures 45.9 Review: Performance, Specs & Cruising Capability

Mar 07, 26 03:22 PM

An expert review of the Allures 45.9 sailboat. Explore technical specs, aluminium construction benefits, and how the lifting keel performs for blue-water cruising. -

Jeanneau Sun Legende 41 Review: Specs, Performance & Buying Advice

Mar 06, 26 12:26 PM

An expert review of the Doug Peterson-designed Jeanneau Sun Legende 41. Discover performance ratios, build quality details, and a buyer's checklist for this classic cruiser. -

O’Day 40 Review: Specs, Performance & Buyer's Guide

Mar 06, 26 04:55 AM

An expert review of the O’Day 40 sailboat. Explore Philippe Briand’s design, performance ratios, common problems to inspect, and how it compares to other 40ft cruisers.