The Cruising Sailboat

and the Lifestyle That Goes with It

There's something rather special about a sailboat...

But there's definitely something really special about a cruising sail boat. Size isn't it - large or small - they all have it. Neither do they have to be stunningly beautiful nor hugely expensive.

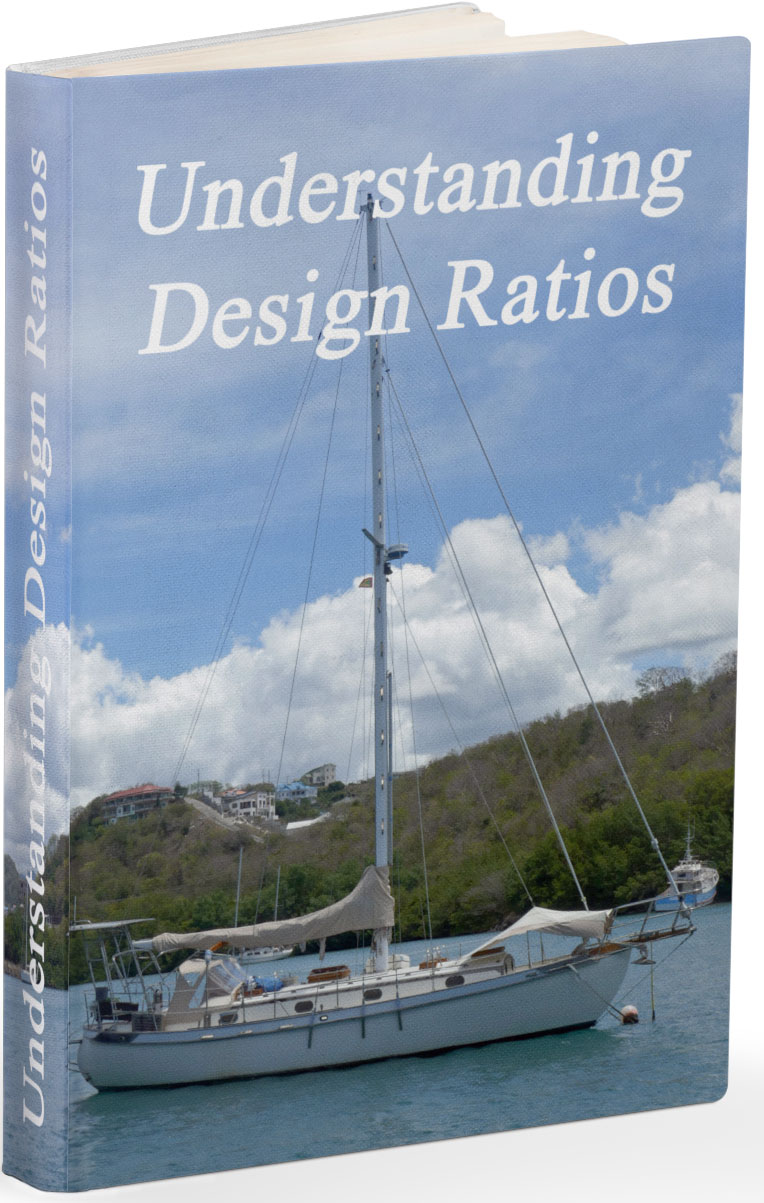

Not huge by any means, but this yawl has definitely got it - whatever 'it' is!

Not huge by any means, but this yawl has definitely got it - whatever 'it' is!It's not about what they are; it's more about what they can deliver - simple pleasure, high adventure or genuine white-knuckle challenge.

Perhaps just a day sail on the lake or a trip along the coast.

A voyage across an ocean maybe, or even a circumnavigation of the world.

And best of all, by utilizing nature's free and sustainable energy resource - the wind.

But be warned - it's addictive. You could end up going the whole hog - getting rid of the shoreside assets, buying a suitable boat and living aboard.

But before you take that gient step, maybe you should charter a sailboat for a couple of weeks, just to be sure?

Either way, you'll find that they represent pure freedom; they're beguiling machines, sailing boats.

Take the beauty below for instance, reaching between the islands in one of the world's favourite cruising grounds - the Windward & Leeward Islands of the Caribbean.

So whether you're a paid-up, certifiable sailboat fanatic familiar with all the nautical jargon and niceties of flag etiquette, or just curious about those of us who are, you're sure to find something of interest by cruising around in this website.

Who knows where you'll fetch up?

Hey, you might even start thinking about buying a sailboat of your own!

The Three Most Popular Types of Cruising Rigs...

The Sloop

Just a headsail and a mainsail - simple and efficient.

The Cutter

A smaller headsail and a staysail makes sail handling easier.

Why the Cutter Rig Sailboat is My First Choice for Cruising.

The Ketch

A second mast with a mizzen sail, for greater versatility.

Why the Ketch is Many Sailors' Favoured Rig for Offshore Cruising

For more on the complexities of sailboat rigging, tahe a look at The A-Z of Sailboat Rigging: A Guide to Standing & Running Rigging.

Sailboat Rig Type Examples:

A Sailboat for Offshore Cruising

Owning a sailing boat, particularly one designed for offshore and ocean sailing, can change your life. With a few gallons of fuel, adequate food and water aboard she'll take you thousands of miles leaving a carbon footprint in her wake that would delight the most ardent environmentalist.

The Tayana 37 is a typical offshore cruising sailboat from the 1970's

The Tayana 37 is a typical offshore cruising sailboat from the 1970'sHey, you can catch your own fish, make your own drinking water from seawater (or collect nature's free offering with a raincatcher) and charge your batteries with a windcharger or solar panels - all without using a drop of fuel!

And you don't need to be on the helm all day - a windvane self-steering gear will keep you on the straight and narrow without drawing a single precious amp from your 12volt battery bank.

With a bluewater boat equipped in this way you could go the whole nine yards, sell your shoreside assets, cast off the shorelines together with the tedium of life ashore and set off on a cruising life of freedom and adventure.

A surprising number of people do just this, but let's not get ahead of ourselves.

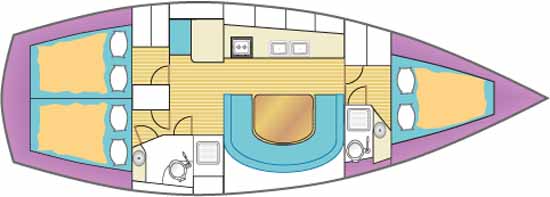

Take the accommodation below decks for example. What might look very attractive at a boat show could prove to be considerably less so when in a seaway.

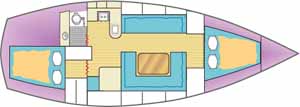

Take a look at the two alternative interior layouts below for instance...

Below Decks

It's here that the interior designer can recreate the appeal of a country cottage or splendor of a minor palace, often in the process making access to fixtures and fittings impossible without major surgery to the boat's interior. It's much better to follow the wise adage that 'form should follow function' and leave all the glitz and glamour to vehicles with wheels on.

The interior layout of a cruising boat is all important. Take a look at these two similar - but different - interior layout options...

One of them is much more suitable for long-distance offshore sailing than the other.

But which one is it, and why?

This, and all other artwork on this page by Andrew Simpson

Multihulls for Cruising

So far we've only mentioned monohulls, but multihull sailboats - both catamarans and trimarans - can make good cruising boats too.

Cruising catamarans like this Lagoon 42 provides cavernous accommodation but are generally not sparkling performers under sail.

Cruising catamarans like this Lagoon 42 provides cavernous accommodation but are generally not sparkling performers under sail. A modern cruising trimaran like this Neel 45 can provide sparkling performance under sail, but the accommodation is nothing like as spacious as would be found in a similarly sized catamaran

A modern cruising trimaran like this Neel 45 can provide sparkling performance under sail, but the accommodation is nothing like as spacious as would be found in a similarly sized catamaran

Our eBooks...

Popular Cruising Sailboats...

Our ever-growing gallery of pics, specs and key performance indicators of many popular cruising boats...

Second-hand Cruising Boats for Sale...

Just click on the images below to see the full details of these cruising boats that are advertised by their owners (not through a broker or other 3rd party) right here on sailboat-cruising.com...

Latest Sailboats Offered for Sale by their Owners...

Recent Articles

-

Beneteau Oceanis 440: Comprehensive Specs & Expert Review

Mar 12, 26 05:29 AM

Discover the Beneteau Oceanis 440. Our expert review covers specs, design ratios, Bruce Farr’s design, common problems, and why it's a top liveaboard choice. -

Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43: Expert Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Mar 11, 26 06:35 PM

An in-depth review of the Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43. We analyse design ratios, build quality, and common buyer issues for this popular 43-foot cruising sailboat. -

Sizing Your Yacht's 12v Domestic Battery Bank | Expert Cruising Guide

Mar 10, 26 07:01 PM

Learn how to accurately size your yacht's domestic battery bank for offshore passages. Calculate ampere-hour demand and manage energy efficiently.