- Home

- Cruising Boats

- Offshore Sailboats

The Desirable Qualities of

Offshore Sailboats

Perhaps we should first try to define exactly what offshore sailboats are. Clearly they’re a step up from sailboats designed for inshore sailing, but what’s the difference between inshore and offshore sailing?

Well, if we can agree that inshore sailing means a coastal passage where the sailboat is always within six hours of a safe haven - six hours being the ‘imminent’ time period in the Shipping Forecast - then it’s fair to say that offshore sailing starts where inshore sailing leaves off.

The European Commission’s Recreational Craft Directive (RCD) has something to say about offshore sailboats too.

It requires that offshore sailboats shall be designed for sea conditions up to Beaufort F8 (wind speeds of 34 to 40 knots) and Significant Wave Heights up to 4m.

Since the Significant Wave Height is the average of the highest 30% of all waves and as individual waves can be twice that, it’s clear that offshore sailing is not for the faint-hearted or inadequately prepared.

But with a little luck, pretty much any reasonably sized cruising sailboat can make an offshore passage, even cross an ocean. And many do, but luck – an unreliable commodity with a tendency to run out altogether – isn’t a sound basis upon which to plan such a venture.

In challenging circumstances, and with little prospect of outside assistance, an offshore sailor must have confidence in the seaworthiness of the vessel beneath his feet.

But this doesn’t mean, as more than a few cruising sailors will have you believe, that only heavy displacement vessels make good offshore sailboats. Overweight, under-canvassed tubs that refuse to sail much closer to the wind than a beam reach and need half a gale to get going at all, do not make ideal offshore sailboats in my view.

Sailing performance that gives a sailboat the capacity to reach a safe haven before a storm arrives, together with the close-winded ability to beat off a lee shore to the safety of deep water, are desirable characteristics indeed.

So Just What Should We Look For In Offshore Sailboats?

Irrespective of whether the sailboat is constructed of GRP, steel, aluminium, wood or ferrocement, or whether it’s heavy or light displacement, or a monohull or multihull, the following three characteristics are fundamental to its suitability as an offshore sailboat.

Seaworthiness

Seaworthiness is a difficult concept to define precisely; many will correctly argue – your insurance company included – that it isn’t just about the sailboat. Crew strength and experience is clearly an influencing factor, as is the extent of stores and equipment carried aboard.

The whole endeavour must be ‘fit for purpose’. But let’s settle on a narrower definition. How about — ‘a seaworthy boat is one that’s capable of looking after her crew in all but extreme conditions?’

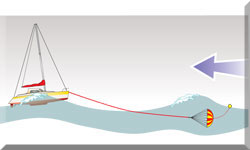

While few boats venturing offshore will ever experience extreme heavy weather unless they go looking for it, it must be said that in such conditions the greatest danger is of being rolled over by a breaking wave.

The ability to resist this alarming prospect is clearly high on the list of seaworthy attributes. The height of a breaking wave capable of capsizing a boat is directly proportionate to the size of the boat, so a good big offshore sailboat is always more seaworthy than a good small one.

So, seaworthiness can’t be described in absolute terms but, in all regards other than size, it’s a function of design. Structural and watertight integrity are fundamental, and in addition to the ability to stay afloat, she must have the windward ability to manoeuvre clear of danger in heavy weather.

She must also be able to provide shelter for her crew, and to recover quickly from a knockdown. Performance then, and comfort, are part of seaworthiness.

Performance

There’s no real argument in favour of slow offshore sailboats – after all you can sail a quick sailboat slowly, but you can’t sail a slow sailboat quickly.

The advantages of sailing quickly are clear, and were brought home to me during a passage from Portugal to Madeira, a distance of 480-odd nautical miles. The internet forecast was for favourable conditions so we planned on a passage time of 80 hours at our usual 6 knots boat speed. We left Portimão on the Algarve shortly after dawn along with another sailboat, agreeing to keep in touch on the VHF and planning to arrive together around midday on the fourth day.

She was about the same length overall as us, but with pretty little overhangs at each end instead of our rather plumb bow and stern.

250 miles out our rather clunky first generation GPS told us we were at 0.00°N and 0.00°W and no amount of tapping and tweaking either at the instrument or the antenna end would persuade it to say otherwise.

The NAVTEX and the barometer were now suggesting that the internet forecast ashore was on the optimistic side, and we could expect things to get worse, which they rapidly did.

I remember getting one sunsight in before the sun became but a lighter patch in a dark sky and the true horizon was lost in a series of approaching wave crests. Now reduced to dead-reckoning, and with the other sailboat left astern and out of VHF range, I was concerned that we may be on our Atlantic crossing a little earlier than anticipated.

Fortunately, the island of Porto Santo appeared pretty much where it should have done, and in the worsening conditions we ducked into the sheltered harbour, much relieved.

But the point of this little tale is that the other, slower sailboat spent a further two nights at sea, hove-to in awful conditions. We met them ashore sometime later — Mary and I looking for a new GPS and our friends trying to find a sailmaker. Our conversation centred around what a difference a knot or two makes.

Seakindliness

Nothing endears a boat more to its crew than the way in which it handles. For example:~

- Offshore sailboats should be easy on the helm and be capable of being trimmed to provide a small degree of weather helm. Those that heel alarmingly and gripe up in every gust — leaving the helmsman no option but to dump the main in a hurry — are a nightmare.

- Offshore sailboats should be responsive to the helm under both sail and power. A sailboat should be capable of tacking up a narrow channel or a river to her mooring, and wriggling in and out of tight marina berths under power.

But not only must offshore sailboats handle well, they must also have a comfortable easy motion underway.

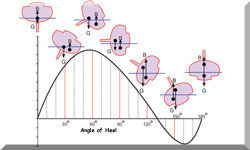

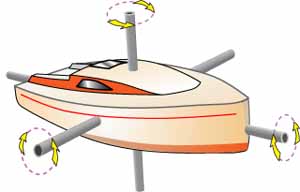

As we saw earlier when discussing stability and righting moment, a boat rotates around three axes.

The combined effect of this movement together with forward motion, and taken as the locus of a single point, is a distorted helix.

Not surprising then, that some of us can feel a little queasy at times.

It’s not only the magnitude of these movements that causes the problem – much of the discomfort is caused by the angular rate of change.

Take the roll motion for example, which probably has the most profound effect on crew comfort and fatigue. It’s not just the extent of the roll angle, but the period of the roll and the ‘jerkiness’ experienced at the ends of the roll. This jerkiness, the roll acceleration, is the force that’s likely to throw you off balance and is the primary culprit in inducing seasickness.

Size of course, has much going for it as far as seakindliness is concerned, as the bigger the offshore sailboat the less inclined it is to leap about.

Second-hand Cruising Boats for Sale...

Just click on the images below to see the full details of these cruising boats that are advertised by their owners (not through a broker or other 3rd party) right here on sailboat-cruising.com...

Latest Sailboats Offered for Sale by their Owners...

Recent Articles

-

The Ultimate Guide to Sailboats: Sloops, Ketches & More

Sep 11, 25 04:42 AM

A comprehensive guide to sailboat types. Learn the differences between monohulls and multihulls, sloops, cutters, ketches, yawls and schooners. -

Essential Sailing Knots & Splicing: The Ultimate Guide

Sep 11, 25 04:41 AM

Master essential sailing knots & splicing with our comprehensive guide. Learn their uses, history, and the anatomy of a perfect knot. -

The A-Z of Sailboat Rigging & Maintenance Explained

Sep 11, 25 04:31 AM

Decode sailboat rigging with our comprehensive guide. We cover everything from standing and running rigging to masts & spars, with expert insights for every sailor.