Mastering Spinnaker Sails for Cruisers: A Guide to Getting Them Up & Down

In a Nutshell

Spinnaker sails for cruisers are a fantastic way to improve downwind performance, especially in lighter winds, without all the stress often associated with racing. For most of us cruising shorthanded, the asymmetric spinnaker (also known as a cruising chute or gennaker) is the perfect choice. It offers some serious performance gains with a much simpler rigging and handling process compared to the conventional, or symmetric, spinnaker. Using a snuffer or sock, you can hoist, douse, and control these powerful sails with confidence.

Table of Contents

- Spinnaker Anatomy & Rigging: A Quick Guide

- What's the Difference Between Asymmetric & Conventional Spinnaker Sails?

- What Are Asymmetric Spinnaker Sails & How Do They Work?

- Do I Need a Bowsprit for an Asymmetric Spinnaker?

- What Are the Main Types of Panel Design & Materials?

- When is a Spinnaker a Cruiser's Friend & When is it Not?

- Avoiding & Handling a Broach

- What's a Snuffer & How Does It Make Life Easier?

- Advanced Handling Techniques for Cruisers

- Spinnaker Equipment & Accessories

- Mastering Spinnaker Trim: Reading the Wind

- Spinnaker Care, Maintenance & Repair

- Including a Spinnaker in Your Sail Inventory

- Frequently Asked Questions

Spinnaker Anatomy & Rigging: A Quick Guide

Before you even think about raising a spinnaker, it's crucial to understand its anatomy. The sail itself has key parts: the head (top corner), the clew (bottom corner), and the tack (the other bottom corner). The luff is the forward edge, the leech the aft edge, and the foot the bottom edge. These elements work together to create the sail's shape and generate power.

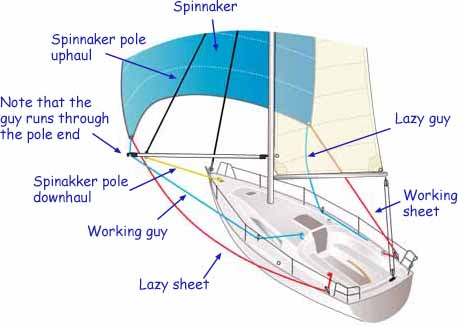

Beyond the sail, understanding the running rigging is paramount. This includes the spinnaker halyard (for raising the sail), the sheets (for controlling the clew), and the guys (for controlling the tack). For a symmetric spinnaker, you'll also have a topping lift (for supporting the spinnaker pole) and a downhaul (for controlling the pole's height). Each line plays a crucial role, and using the correct size and type for your boat is essential for safety and performance. Don't forget the hardware: blocks, shackles, and pole fittings all must be in top condition.

Masthead versus Fractional Rigs

Before choosing a spinnaker, it's important to know what kind of rig you have. On a masthead rig, the forestay goes all the way to the top of the mast. On a fractional rig, the forestay is attached to a point partway down the mast.

This skipper has chosen to fly a conventional spinnaker from the forestay attachment point rather than an asymmetric from the masthead.

This skipper has chosen to fly a conventional spinnaker from the forestay attachment point rather than an asymmetric from the masthead.This makes a big difference for spinnakers. A conventional spinnaker is designed to be hoisted to the masthead to maximise sail area, so it's a great choice for a masthead rig. With a fractional rig, you have the option of flying a spinnaker from the top of the mast or from the forestay's attachment point. This is why many cruisers with fractional rigs prefer an asymmetric spinnaker, as they're generally flown from the masthead and offer fantastic reaching performance with a simple setup.

What's the Difference Between Asymmetric & Conventional Spinnaker Sails?

For a lot of us cruisers, the sight of a full-blown racing spinnaker, squared off with a pole, is a spectacle best left to the pros. Yet, sailing dead downwind in light winds with just a genoa can be painfully slow and inefficient. That's where spinnakers really come into their own. The main difference between a conventional and an asymmetric spinnaker is in how you rig them, which in turn determines their shape and function.

How to rig a conventional spinnaker

How to rig a conventional spinnakerA conventional, or symmetric, spinnaker is attached to a pole that's squared off to the wind. This allows the sail to be set directly in front of the boat, operating in clear air, and it's what makes them so effective for sailing dead downwind. But let's be honest, the complexity of managing the pole, guy, uphaul, and downhaul lines can be a proper challenge for a small crew.

An asymmetric spinnaker, on the other hand, doesn't use a pole. Instead, its tack is attached to the boat's bow or a short bowsprit, and its clew is controlled by a sheet.

This design means the sail can't be set directly in front of the boat, but rather to one side or the other. It's a much simpler setup and a lot less intimidating to rig and handle.

One final difference is the size and shape. An asymmetric sail has a longer luff than its leech and is about 25% smaller in area than a conventional spinnaker. It's still, however, about twice the size of a typical 150% genoa.

| Conventional Spinnaker | Asymmetric Spinnaker | |

|---|---|---|

| Riding Position | Dead downwind to a broad reach | Reaching to a broad reach |

| Rigging | Requires a spinnaker pole, uphaul, downhaul and guy | No spinnaker pole required. The tack is attached to the bow or a short bowsprit |

| Shape | Symmetric, with luff and leech the same length | Asymmetric, with a longer luff than leech |

| Performance | Can sail dead downwind; complex to handle | Less effective dead downwind; easier to trim and handle |

| Ideal For | Racing and long offshore legs in consistent wind | Shorthanded cruising; day sailing; reaching angles |

What Are Asymmetric Spinnaker Sails & How Do They Work?

Sometimes they're called a gennaker, cruising chute, or multi-purpose spinnaker, and they're what many of us cruisers really need for better performance. You hoist them on a spinnaker halyard and control them with a sheet led through a block on the quarter. They can give you spinnaker-like performance on all points of sail from a close-reach to a broad reach.

As an experienced sailor, I can tell you the real beauty of the asymmetric is its versatility. When you're close-reaching, you can pull the adjustable tack line down, tightening the luff and encouraging the sail to act more like a big genoa. They're at their operating limit when the wind's on the quarter; any further aft and they'll get blanketed by the main and lose all their power.

A word of warning: you should never be tempted to fly one on its own. Without being able to use a full main to blanket it, you'll have a devil of a job getting it down safely, especially in a gust.

Do I Need a Bowsprit for an Asymmetric Spinnaker?

When you rig one correctly, your asymmetric spinnaker's tack is led back to the cockpit through a block at the stemhead. However, on many cruising boats, the foredeck and pulpit just weren't designed with these sails in mind. There might not be a good point ahead of the forestay to attach a tack line block, and if there is, the line could chafe against the pulpit or the bow anchor.

A short bowsprit, like a retractable one, solves these problems perfectly. By setting the sail further forward, it operates in clearer air and is more efficient as a result.

At least one spar manufacturer has recognised this and produced a very neat device that attaches to a ring on the foredeck and is removable, so you won't get charged for it in marinas.

What Are the Main Types of Panel Design & Materials?

There are three primary designs for spinnaker sails, each with a slightly different application. All designs feature a radially cut head for strength and stability. These sails are typically made from lightweight nylon, with different material weights (measured in ounces) available depending on their intended use. A heavier cloth will be more durable but less effective in light winds.

- Starcut: This design has a slightly flatter cut, so it's optimised for reaching. It's a good choice if you do a lot of reaching.

- Radial Head: Cut fuller than the starcut, with wider shoulders, the radial head is more stable downwind. However, it's less stable than the starcut when sailing closer to the wind.

- Tri-radial: Considered the best all-rounder for most cruisers, the tri-radial is easy to trim and has a wide operating range, typically from 70° to 160° of the wind.

The aspect ratio, which is the ratio of the spinnaker's height to its width, also influences its performance. High aspect ratio spinnakers are taller and narrower, offering better upwind performance and stability in lighter winds. Low aspect ratio spinnakers are wider and shorter, providing more power in stronger winds and downwind conditions.

When is a Spinnaker a Cruiser's Friend & When is it Not?

I've used these sails in a variety of conditions. In my experience, hoisting a spinnaker is a balance of performance against safety and effort.

A spinnaker is your best friend when:

- The wind is light (typically under 15 knots) and on or aft of the beam.

- You're sailing on a long, single leg without a lot of gybes.

- You've got enough crew to manage the hoist and douse safely.

- You're sailing in an area with a clear lee shore and no risk of sudden wind shifts.

However, a spinnaker can turn into a liability when:

- The wind is gusty or building. If you let it get out of control, heavy rolling can develop, which can lead to a broach. A broach to leeward is a frightening experience, but a windward broach (which puts the spinnaker pole into the water and can cause a crash gybe of the boom and mainsail) can have very serious consequences indeed.

- The crew is tired or inexperienced. Spinnakers demand you stay alert and react quickly, especially if you don't have a snuffer.

- You're sailing in confined or crowded waters. The extra power and sail area can be a real hazard in areas with lots of traffic or obstacles.

For me, the key is knowing your boat's limits, and your own. A well-managed asymmetric is a joy, but trying to fly a full conventional spinnaker in a squall without an experienced crew is a recipe for trouble.

Avoiding & Handling a Broach

The thrill of sailing with a spinnaker is undeniable, but it comes with a potential hazard: the spinnaker broach. This is an uncontrolled rounding up, often initiated by a combination of factors. The large surface area of the spinnaker, positioned downwind, creates a powerful turning force. When this force becomes unbalanced, the boat can spin out of control.

What Causes a Broach?

A broach is typically caused by one or more of these factors: excessive heel, sudden wind shifts, improper trim, or steering errors. In confused or large seas, waves can disrupt the boat's balance and make it harder to maintain control.

The dreaded spinnaker broach

The dreaded spinnaker broachProactive Prevention

Prevention is the best cure. A few proactive strategies can significantly reduce the risk:

- Choose the right spinnaker for the prevailing wind strength and sea state.

- Maintain proper trim by understanding how to adjust the halyard, sheets, and guys to optimize the spinnaker's shape.

- Use a preventer line on the boom to avoid accidental gybes, which can often initiate a broach.

- Maintain an active watch and active helmsmanship to anticipate changes.

Handling a Broach

Even with the best preparation, broaches can still happen. The most crucial step is to ease the spinnaker sheet. This depowers the sail and reduces the turning force. Simultaneously, head upwind. Steering the boat towards the wind reduces the heel and helps you regain control. If possible and safe, release the spinnaker pole. Throughout the process, crew coordination is essential. Clear communication and coordinated action will help you manage the situation effectively.

What's a Snuffer & How Does It Make Life Easier?

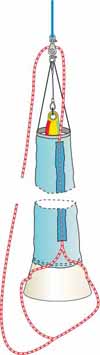

While racing crews will often just 'throw the kite up' directly from the spinnaker bag, we cruisers should be giving a collective vote of thanks for the spinnaker snuffer, or sock.

This simple device makes hoisting and dousing a spinnaker a manageable task for even a small crew.

A spinnaker snuffer is a long canvas sock with an opening at the bottom, operated by an endless line. The sail gets packed inside the sock on deck before you hoist it. The process works like this:

Hoisting:

- Hoist the sail in the snuffer to its full height.

- Secure the tack line, then ease the snuffer line.

- As you ease the snuffer line, the sock will lift to the head of the sail, letting the sail fill with wind.

- Once the sock is fully raised, trim the sheet and you're good to go.

Dropping:

- Ease the sheet, letting the sail collapse.

- Haul on the snuffer line to bring the sock down over the sail.

- Once the sail is secure and controlled by the snuffer, you can lower it to the deck in a controlled way.

Advanced Handling Techniques for Cruisers

While a snuffer is the safest method for dousing a spinnaker, it's also good to know a few alternative techniques, particularly when sailing with a small crew. The takedown behind the main is a reliable method that uses the mainsail to help blanket the spinnaker and take its power out. To do this, the helmsman turns the boat slowly downwind, and the crew eases the spinnaker sheet while pulling the sail down behind the mainsail, which shields it from the wind. This technique is especially useful in moderate winds where a snuffer might be difficult to handle.

Another key skill is gybing an asymmetric spinnaker. Most of us cruisers prefer the inside gybe, where the sheet is passed between the forestay and the luff of the spinnaker. For shorthanded sailing, this is less likely to result in a wrap around the forestay than an outside gybe.

Spinnaker Equipment & Accessories

Proper spinnaker work relies on the right gear. For symmetric spinnakers, a spinnaker pole is a crucial piece of equipment, enabling the sail to be set directly across the wind. Proper rigging and handling of the spinnaker pole are essential for safe and efficient spinnaker work.

Both symmetric and asymmetric spinnakers require a good set of sheets, and a tack line for the asymmetric. Choosing the right size and material for these lines ensures smooth operation and prevents chafe or breakage. High-quality blocks and hardware are also crucial for smooth spinnaker operation and prevent chafe or breakage. Ensure that the blocks and hardware you choose are appropriately sized for your boat and the loads they will bear.

Mastering Spinnaker Trim: Reading the Wind

The spinnaker is the key to unlocking true downwind performance. But simply hoisting it isn't enough—to truly harness its power, you need to master the art of spinnaker trim.

Understanding the Forces at Play

Before you start tweaking lines, it's crucial to understand the fundamental forces acting on your spinnaker. Apparent wind is the wind you feel on the boat, a combination of the true wind and the boat's motion. It's this apparent wind that dictates how you trim the sail. The spinnaker generates power through a combination of lift and drag. The goal of proper trim is to maximize lift while minimizing drag.

Adjusting the Spinnaker: The Primary Controls

Trimming a spinnaker involves manipulating several key lines. The spinnaker halyard controls the luff tension and overall sail shape. Tightening the halyard generally flattens the sail, while easing it allows the luff to become fuller. The spinnaker sheet is arguably the most important control. It dictates the clew's position and, consequently, the sail's angle of attack. The spinnaker guy (for symmetric spinnakers) controls the tack, influencing the sail's projection and overall shape.

Fine-Tuning the Spinnaker

While the primary controls get you in the ballpark, fine-tuning is what unlocks true performance. Telltales attached to the spinnaker's luff provide valuable feedback on airflow. These small pieces of yarn or cloth indicate whether the airflow is smooth and attached or if it's separating. Adjust your trim to keep the telltales flowing evenly on both sides of the sail. Leech sag refers to the curvature of the spinnaker's trailing edge; observing it can tell you whether the sail is over-trimmed or under-trimmed. Finally, boat speed is the ultimate indicator of proper spinnaker trim.

Spinnaker Care, Maintenance & Repair

Proper care is essential if you want to extend the life of your spinnaker.

- Checking for Chafe: Regularly inspect the sail, especially along the leech and at the corners, for any signs of chafe where it might've rubbed against rigging.

- Small Repairs: For small tears, a quick patch with rip-stop sail tape can prevent them from getting bigger. Always carry a small repair kit with you.

- Professional Inspection: I'd recommend having your spinnaker professionally inspected by a sail loft every few years. They can spot and repair damage you might miss and ensure the sail's properly serviced.

- Storing Your Sail: Always make sure the sail is fully dry before packing it away to prevent mildew, which can damage the cloth.

There's more on this topic at A Sailor's Guide to Sail Maintenance

Including a Spinnaker in Your Sail Inventory

For long-distance cruisers, a well-thought-out sail inventory is critical. A spinnaker's a high-performance sail, but it doesn't replace a reliable cruising headsail. Here's how it fits into your inventory:

- Headsails: You'll likely have a furling genoa as your primary headsail for most points of sail. For downwind work, a poled-out genoa can be effective but isn't as efficient as a spinnaker.

- Twin Headsails: Some cruisers opt for a twin headsail or "wing-on-wing" setup for long passages directly downwind. While this is very stable, it requires more rigging and is generally slower than a conventional spinnaker.

- The Spinnaker's Role: The spinnaker's role is to give you a significant speed boost on downwind or reaching points of sail, especially in lighter winds. It's a performance-enhancing tool, not a primary sail for everyday use.

Spinnakers are just one part of the whole sail power puzzle. To learn more about how different types of sails work together to power your boat and the fundamentals of sail design, rigging, and sail handling, explore our comprehensive Guide to Sailboat Sails: Powering Your Passage.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

Are spinnakers difficult to handle for a small crew?

Are spinnakers difficult to handle for a small crew?

Asymmetric spinnakers, especially when used with a snuffer, are very manageable for a small crew of two or even single-handed sailors. The conventional spinnaker's much more challenging and is best suited to a larger, more experienced crew.

Can I use a spinnaker without a snuffer?

Can I use a spinnaker without a snuffer?

Yes, it's possible, but it's not recommended for most of us cruisers. A snuffer makes the process of hoisting and dousing much safer and more controlled, significantly reducing the risk of the sail getting away from you.

What is a 'chute' or 'cruising chute'?

What is a 'chute' or 'cruising chute'?

A cruising chute's another name for an asymmetric spinnaker. We often use the term to differentiate it from a racing spinnaker and to highlight that it's designed for cruisers who value ease of use.

How do I pack a spinnaker for easy hoisting?

How do I pack a spinnaker for easy hoisting?

The best way is to flake the sail neatly and pack it into a bag from the head down, leaving the tack and clew on top. This ensures that the tack and clew are the first parts of the sail to come out, ready to be attached to the boat.

What material are spinnakers made from?

What material are spinnakers made from?

Spinnakers are typically made from lightweight nylon. The material's low weight and high strength allow the sail to be cut into a full, three-dimensional shape that catches the wind really effectively.

Recent Articles

-

Island Packet 40 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Feb 09, 26 05:05 AM

An in-depth review of the Island Packet 40 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and real-world cruising performance for this legendary blue-water cruiser. -

Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper Review: Specs, Performance & Ratios

Feb 04, 26 07:25 PM

A comprehensive review of the Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper sailboat. We analyse design ratios, interior layout, and performance for prospective cruising owners. -

Self-Tacking Headsails: Track Systems vs Hoyt Jib Booms

Feb 03, 26 06:26 AM

Master the mechanics of self-tacking headsails. We compare traditional club-footed rigs, curved tracks, and the superior Hoyt Jib Boom for offshore sailing.