Why Dacron Sails are Still the Best Choice for Cruising

In a Nutshell

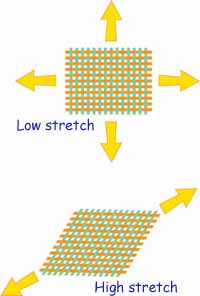

A sail's performance is determined by two main factors: the modulus (a measure of the fibre's resistance to stretch) and the tightness of the weave. Dacron provides a good balance of both, ensuring the sail holds its designed shape without excessive stretch. For the cruising sailor, this translates to predictable, reliable performance without the significant expense of high-end materials.

Table of Contents

What is Dacron Sailcloth & Why is it so Popular?

Dacron is the brand name for a type of woven polyester fibre. It has been the most widely used sailcloth for cruising boats since the 1950s, largely replacing traditional cotton. Its popularity stems from a combination of desirable properties: good UV resistance, fatigue resistance (the ability to withstand repeated flexing), and abrasion resistance, all at a comparatively low cost.

Polyester yarn is woven into a fabric on a loom, a process that is significantly more affordable than creating laminated sails which are made by gluing together layers of plastic film and reinforcing fibres. This cost-effectiveness is a key reason why Dacron continues to be the default choice for cruising sailors.

How does Sail Finishing Impact Performance & Longevity?

Dacron's inherent properties are significantly enhanced by the finishing processes applied after weaving. These are crucial for protecting the fabric from the marine environment and optimising performance. The two primary finishing techniques are resin treatments and calendering.

Resin Treatments

Resin treatments involve applying a protective layer of resin to the fabric. This process fills the gaps between the woven fibres, creating a barrier that enhances the sail's properties. Different resins offer different benefits:

- Acrylic resins are flexible and offer good UV resistance, making them suitable for casual cruising.

- Polyurethane resins provide excellent abrasion resistance and water repellency, ideal for sails that are exposed to harsh conditions.

- Epoxy resins offer superior strength and stiffness, commonly used in performance-oriented sails.

The resin treatment protects the sail from UV degradation, which breaks down the polyester fibres, and from mildew, which thrives in damp conditions. A well-treated sail also repels water, preventing it from becoming waterlogged and heavy, which would negatively affect performance.

Calendering

Calendering is a mechanical process where the Dacron fabric is passed through heated rollers under high pressure. This flattens and compacts the fibres, resulting in a smoother, denser surface.

- Reduced Air Permeability: The calendering process reduces the fabric's porosity, meaning less air can pass through the sail. This is essential for maintaining the sail's designed shape and efficiency, particularly in light winds.

- Improved Smoothness: A smoother surface reduces friction and improves airflow over the sail.

- Enhanced Luster: Calendering gives the sail a polished, refined appearance.

While resin treatments prioritise durability, calendering focuses on performance. Often, a combination of both is used to create a sail that is both durable and has excellent shape retention.

I remember discussing this with a sailmaker in Plymouth; he likened the combination to putting a robust coating on a finely engineered tool—the coating protects, and the engineering ensures it works perfectly.

What are the Main Types of Dacron Weaves?

Not all Dacron is woven the same way. The weave of the fabric is critical to how a sail performs and is directly related to the sail's intended purpose. The two main components are the warp yarns (running lengthwise) and the fill or weft yarns (running crosswise).

Sailcloth warp and weft

Sailcloth warp and weftBalanced Weave

The balanced weave is the most traditional type, where the warp and fill yarns have an equal count. It is most commonly used for cross-cut sails, where the panels are laid out horizontally, perpendicular to the leech.

Pros:

- Cost-effective & Durable: The simple, uniform construction makes this the most affordable and robust option for most cruising applications.

- Forgiving: It handles a wide range of conditions well, making it a great all-purpose choice.

Cons:

- More Stretch: Balanced weave sails tend to stretch more than other weaves, leading to less precise sail shape control.

High-Aspect Weave

The high-aspect weave features a higher count of warp yarns than fill yarns. This design is specifically engineered to resist stretch along the length of the sail, making it ideal for tall, narrow mainsails and jibs.

Pros:

- Improved Shape Holding: It maintains the designed sail shape better, leading to improved performance, especially in moderate to strong winds.

Cons:

- Higher Cost: More expensive than balanced weave due to the specialised construction.

Tri-Radial Weave

Primary load paths

Primary load pathsThe tri-radial weave is the pinnacle of Dacron sail construction for performance. It uses a complex panel layout where the panels radiate from the corners of the sail. This design aligns the yarns precisely with the primary load paths.

Pros:

- Maximum Performance: Delivers superior shape-holding and performance over a wider range of wind conditions.

Cons:

- Highest Cost: The intricate construction makes tri-radial sails the most expensive Dacron option.

Here's a quick summary of the different Dacron weaves:

| Weave Type | Best For | Key Characteristic | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Weave | Casual Cruising & General Purpose | Uniform yarn count (warp & fill) | Cost-effective & Durable, but stretches more. |

| High-Aspect Weave | Performance Cruising | Higher warp yarn count than fill yarn | Better shape holding, but higher cost. |

| Tri-Radial Weave | Racing & High-Performance Cruising | Panels radiate from corners, aligning with loads | Superior shape holding, but highest cost. |

How Does Dacron Compare to Other Sailcloth Materials?

While Dacron is the standard for cruising, other materials are available, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. These are typically laminated fabrics, made by bonding layers of film and reinforcing fibres.

- Vectran/Polyester Woven Hybrid: Vectran is an aromatic polyester fibre that’s often woven into Dacron to create a high-performance woven cloth. It offers a much higher modulus (five times that of pure Dacron) for excellent shape-holding and reduced stretch. It's an excellent choice for performance cruisers who want the shape stability of a laminate without sacrificing the durability and ease of handling of a woven sailcloth.

- Aramid Fibres (e.g., Kevlar, Twaron): These are very low-stretch and are often used for high-end racing sails. They have a modulus many times greater than polyester. However, they are significantly more expensive and are often inferior to Dacron in UV, fatigue, and abrasion resistance.

- High Modulus Poly-Ethylene (HMPE) Fibres (e.g., Spectra, Dyneema): These fibres are lightweight, durable, and have excellent fatigue, UV, and abrasion resistance. They have a higher modulus than polyester, making them a popular choice for performance cruising sails.

- Nylon: Known for being very lightweight, nylon is traditionally used for spinnakers due to its elasticity. However, its poor stretch resistance makes it unsuitable for upwind sails.

Dacron's primary advantage is its balanced performance across all key metrics—durability, longevity, stretch resistance, and cost. While other materials may excel in one specific area (e.g., low stretch), they often compromise on others (e.g., durability or cost), making Dacron the most sensible choice for the cruising sailor who needs reliability over all-out performance. For a broader overview of sail types and materials to power your passage, be sure to consult our comprehensive Guide to Sailboat Sails: Powering Your Passage.

Sail Care & Maintenance: A Guide to Extending Your Sail's Life

Proper care and maintenance are vital for getting the most out of your sails, regardless of the fabric. I've found that a proactive approach, rather than a reactive one, saves both time and money in the long run.

Regular Inspection: Catching Problems Early

Before and after each use, give your sails a once-over. A more detailed inspection should be carried out seasonally. Pay close attention to:

- Seams & Stitching: Look for loose or broken threads. UV-resistant thread is crucial for longevity.

- Chafing: Check for wear where the sail rubs against rigging, spreaders, or stanchions.

- UV Damage: This appears as fading or discoloration and indicates a weakening of the fabric.

- Mildew: Mildew shows as dark stains and can weaken the sailcloth if left untreated.

Catching a small tear or a bit of loose stitching early can prevent a major, costly repair down the line.

Cleaning: Removing Salt & Grime

Salt and dirt degrade sailcloth over time. The best way to clean your sails is with fresh water, a mild soap, and a soft brush. Never use harsh chemicals or bleach, which can damage the fabric and its protective coatings. For stubborn mildew, a diluted solution of white vinegar or a specialised mildew remover can be effective, but always rinse thoroughly afterward.

Repairing Minor Damage

Small tears and rips can often be fixed with a self-adhesive sail repair tape. For larger tears or damaged stitching, a professional sailmaker is your best bet. They have the expertise to restore your sail correctly, ensuring it remains strong and reliable. I learned the hard way that a quick fix at sea is no substitute for a professional repair. A good sail repair kit is essential for any offshore sailor.

Proper Storage

Sails should always be stored clean and dry in a cool, well-ventilated area. Avoid folding them along the same creases to prevent weakening the fabric. A sail bag or storage container is a good idea to protect them from dust and UV radiation.

For more on this topic you might wany to take a look at our article A Sailor's Guide to Sail Maintenance.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

FAQs

What is the difference between Dacron and laminated sails?

What is the difference between Dacron and laminated sails?

Dacron is a woven polyester fabric, prized for its durability and low cost. Laminated sails are made by bonding multiple layers of film and reinforcing fibres, offering superior shape-holding and lighter weight but at a higher cost and with a typically shorter lifespan due to a higher susceptibility to delamination.

How long do Dacron sails last?

How long do Dacron sails last?

With proper care, a good quality Dacron sail can last anywhere from 10 to 20 years or more, depending on usage, sailing conditions, and how well it is maintained. UV exposure is the biggest enemy of sail life.

Can I clean my sails myself, or should I hire a professional?

Can I clean my sails myself, or should I hire a professional?

For routine cleaning, you can do it yourself with fresh water and mild soap. For deep stains or a seasonal clean, a professional sail laundry service can be a worthwhile investment. They have the right equipment and knowledge to clean the sails without damaging the fabric or stitching.

When should I replace my Dacron sails?

When should I replace my Dacron sails?

You should consider replacing your sails when they lose their designed shape, no longer hold a good airfoil, or show significant signs of UV degradation, tears, or a general weakening of the fabric. A professional sailmaker can help you determine if a repair is feasible or if it is time for a new sail.

Do I need a UV cover on my furling headsail?

Do I need a UV cover on my furling headsail?

Yes, a UV cover in the form of a sacrificial strip is highly recommended for any furling headsail left hoisted on the forestay. It protects the sail from constant sun exposure, which is the primary cause of fabric degradation.

Resources Used

- Doyle Sails. Dacron: The Cruiser's Choice

- UK Sailmakers. Dacron Deconstructed: Not All Sailcloth is Equal

- North Sails. Sail Care & Maintenance Tips

- Sailrite. How to Clean Sailcloth & Marine Canvas

Recent Articles

-

CSY 44 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 10:41 AM

An in-depth review of the CSY 44 sailboat. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this heavy-displacement cruiser remains a top choice for ocean voyagers. -

Irwin 54 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 07:24 AM

An expert review of the Irwin 54 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, cruising capabilities, and why this shoal-draft yacht is a liveaboard favourite. -

Beneteau Oceanis 473 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Guide

Feb 20, 26 04:49 AM

An in-depth review of the Beneteau Oceanis 473. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this Groupe Finot design remains a top offshore cruising choice.