- Home

- Cruising Boats

- Displacement Hull

A Heavy or a Light Displacement Hull for Offshore Cruising?

In the early days of sailboat cruising, heavy displacement hull forms were the only choice for long-distance offshore cruising, solely because light materials for the hulls, spars, rigging and all the other fittings and equipment that go to make up a sailboat just weren't available.

Displacement Length Ratios:

Under 90 - Ultralight;

90 to 180 - Light;

180 to 270 - Moderate;

270 to 360 - Heavy;

360 and over - Ultraheavy;

These days, with the advent of exotic composite laminates and lightweight fittings, super-strong and ultra-light displacement hull forms are regularly seen crossing the world's oceans.

But there are plenty of sailors around that still favour the easy motion of heavy displacement hulls for offshore cruising, cheerfully conceding the extra days spent at sea for the benefit of increased comfort in rough seas.

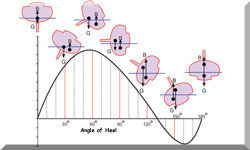

Elsewhere on this website we've seen how displacement has a consequential influence on stability, performance and comfort. Now let's turn it around and look at the strengths and weaknesses that each one - from ultra-heavy to ultra-light displacement hull types - has to offer.

Heavy and Ultra-Heavy Displacement Hulls

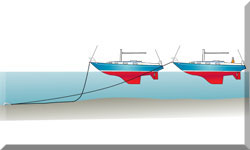

With Displacement/Length ratios of 360 plus, ultra-heavy displacement hull styles have fewer devotees these days, though for passionate cruising traditionalists it's de rigueur. Heavy displacement sailboats of this type will have a full (or long) keel, which will bring with it some benefits - and some significant limitations.

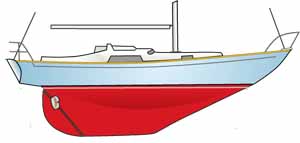

Underwater profile of a heavy-displacement long-keel sailboat

Underwater profile of a heavy-displacement long-keel sailboatIn light winds, a boat of this type will sail slowly - if at all - due to the hull drag caused by its high wetted area and the power required to shift its massive weight.

It will only just be getting into its stride when other more moderate types are taking in reefs.

Apart from its contribution towards a sailboat's stability the next most important function of a keel is to resist leeway. Unfortunately, long, low aspect ratio keels aren't very good at this so they must make up in area what they lack in efficiency.

To counteract the hull drag caused by the surface area more sail area is required, so to enable the boat to stand up more ballast is needed, which is why long-keelers need to be heavy and why they are often underpowered.

My first 'proper' cruising boat (a Nicholson 32 Mk10, 'Jalingo II') with a length/displacement ratio of 394 was a craft of this type. Jalingo's long keel kept her tracking as if on rails, but it was important to keep plenty of way on to get her through the wind when a tack was called for. Her motion underway was sedate, and as comfortable as you could get for a boat of this size. Her vee'd forward sections gave a soft ride but she did show a tendency to bury her bows, making her a little wet at times.

But my enthusiasm for her excellent directional stability at sea largely evaporated during close-quarters manoeuvring. She was a nightmare in a marina where going astern with any degree of directional certainty was well-nigh impossible.

When heeled, the general symmetry of the immersed hull section will mean they should remain well balanced at high heel angles, but the barn door proportions of their unbalanced rudders and the fact that they are often raked off the vertical make them heavy on the helm at all times.

With their relatively shallow draft, protected propeller and rudder these boats will take the ground well, and should breeze over floating ropes and nets without problem.

The high load carrying capacity of heavy displacement hulls will be greatly appreciated by live-aboard sailors, which together with their other attributes will probably make them best suited for those sailors with ambitions to spend much of their time offshore in remote areas of the world.

But for those of us who are more inclined to spend our time island hopping in the Caribbean and Mediterranean, and cruising offshore in Europe and the USA their sluggish performance will make them less attractive.

A Moderate Displacement Hull

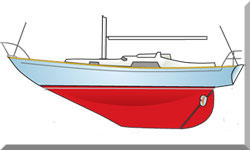

Moderate displacement sailboats are a natural development of the heavy displacement hull types, with a moderate length fin keel and a separate rudder which is either transom hung or supported on a skeg.

On GRP boats, the fin keel may be part of the hull moulding and have its ballast encapsulated within. This avoids the need for keel bolts, and the corrosion and security issues often associated with them.

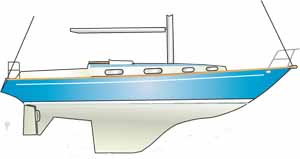

Underwater profile of a medium displacement fin-and-skeg sailboat

Underwater profile of a medium displacement fin-and-skeg sailboatAlthough still on the heavy side by modern standards, with a Displacement/Length Ratio of around 300, this type remains a firm favourite with many long-distance cruisers.

Performance, whilst not of the 'ocean greyhound' nature, should be adequate in most conditions and owing to the separation of keel and rudder, manoeuvrability under both power and sail will be much improved.

For a given Sail Area/Displacement ratio her sail area will be less than for the heavy displacement type, making her easy to handle for a small crew. Directional stability and balance will be dependent on the quality of the design, and there's no reason why both shouldn't be excellent.

Light Displacement Hull

Driven partially by the need for economy in a competitive market - lighter means less material - and an increasing demand for better performance, more and more yachts are falling into this category.

Typically with a Displacement/Length Ratio of around 200, a modern light displacement production boat - often dubbed a 'cruiser/racer' - will sport a medium aspect ratio fin keel'. The rudder will be either transom hung, or be supported by a short skeg, or be a cantilevered spade type. The underwater shape will be dinghy-like, with minimal overhangs at bow and stern to maximise waterline length.

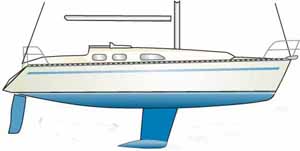

Underwater profile of a light displacement fin keel and spade rudder sailboat

Underwater profile of a light displacement fin keel and spade rudder sailboatArtwork by Andrew Simpson

A lot of ballast is clearly not an option for a light displacement boat so much of its stability is gained through increased beam.

This means that when excessively heeled the asymmetry of the immersed hull sections coupled with the broad beam carried well aft can make them hard on the helm.

Much is to be gained by reefing these boats early and sailing them fairly flat. Performance will be brisk in nearly all conditions, especially off the wind, when hull speed may well be exceeded with a light displacement hull of this type.

Sailing hard on the wind in vigorous conditions will be less comfortable than in a heavier displacement craft. The flatter forward sections can tend to pound, and the ride is likely to be on the lively side.

Apart from beating to windward in heavy weather they are a delight to sail, pointing high and tacking through the wind with ease - and passage times shouldn't be disappointing.

Handling under power, both ahead and astern, will be good. Except, that is, when at low speed in a crosswind. This was brought home to me during our early days with Alacazam (our custom yellow and white wood-epoxy sailboat shamelessly featured in the logo of this website), when motoring astern out of a marina berth in Leixões in Portugal. The wind was blowing from the direction I wanted to go, but as soon as I cleared the berth and put the helm over the wind blew the bow off so I was pointing at the next berth down.

Someone once said that the height of stupidity is doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting a different result. I thought of this as I found myself zig-zagging sideways down a cul-de-sac, greeting a series of worried looking crews on the way.

Fortunately, Alacazam steers astern almost as well as ahead so the obvious solution - which fortunately occurred to me before we reached the seawall at the end - was to let the bow blow around and motor out astern past my visibly relieved audience until there was enough room to turn. Another lesson learned.

The load-carrying capacity of smaller light-displacement boats can be a concern. Clearly if you load, say, 1,500lb of stores and equipment on a 25ft boat with a Displacement/Length Ratio of 200 it will have a greater effect than if you loaded the same amount onto a forty footer of the same Displacement/Length Ratio. The 25 footer's Displacement/Length Ratio would increase to 242 and the forty footer's to 210 - obviously a more performance-sapping penalty for the smaller boat.

Ultra-Light Displacement Hull

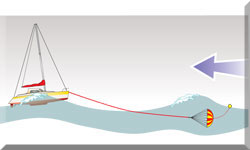

These ultra-light displacement boats (ULDBs) are probably at least one step too far for the vast majority of offshore cruising sailors. Sharing many of the characteristics of the previous category but more so, these will be beamier, lighter and deeper drafted. Keels will be high-aspect ratio and of such depth to prevent anchoring anywhere near the beach. Performance in the right conditions though will be awesome.

These types will readily unstick themselves from the limitations of hull speed and plane like dinghies, and it should come as no surprise that Ted Brewer's comfort ratio isn't high on the list of design considerations.

To build such a light displacement hull whilst making her sufficiently strong calls for exotic materials and hi-tech building techniques, both of which come with a high price. So much so that cruising versions are generally owned by people with Lamborghinis, and backyards the size of Regents Park.

Optimum performance, handling and comfort can't all be found at the same place on the sliding scale of displacement.

Displacement, or more accurately the Displacement/Length Ratio has a greater influence on the way in which a boat behaves in a given set of conditions than any other parameter, and should be a crucial consideration for a prospective buyer.

Whilst boats at the heavy end will have a more comfortable motion, passage times will be slower and handling more cumbersome. At the other end, the blistering performance of a ULDB will shake your fillings loose.

Somewhere though, between these two extremes, lays your ideal heavy/light displacement hull compromise.

Recent Articles

-

Albin Ballad Sailboat: Specs, Design, & Sailing Characteristics

Jul 09, 25 05:03 PM

Explore the Albin Ballad 30: detailed specs, design, sailing characteristics, and why this Swedish classic is a popular cruiser-racer. -

The Hinckley 48 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:44 PM

Sailing characteristics & performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley 48 sailboat... -

The Hinckley Souwester 42 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:05 PM

Sailing characteristics and performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley Souwester 42 sailboat...