- Home

- Choosing Accessories

- Parachute Sea Anchor

Parachute Sea Anchors

and Drogues

Most offshore sailors view parachute sea anchors and drogues much like storm jibs and trysails; items we should have aboard but hope we're lucky enough never to have to use them.

But luck's an unreliable commodity at best, with a tendency to run out altogether - and usually at the most inopportune time.

So if you're venturing far offshore, there's no doubt you should have aboard either a sea anchor or a drogue.

The basic difference difference is that the para-anchor is deployed from the bow and will stop the boat head to wind and sea, and the drogue is deployed from the stern, slowing the boat down considerably.

With one eye on your bank balance, you'll probably choose either one or the other, but which one?

Parachute Sea Anchors

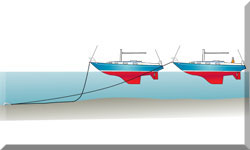

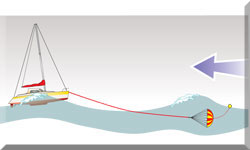

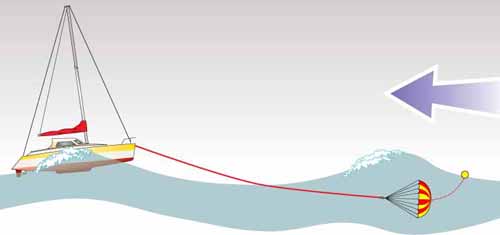

A parachute sea anchor is always deployed from the bow - never the stern.

A parachute sea anchor is always deployed from the bow - never the stern.Artwork by Andrew Simpson

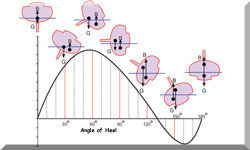

Many offshore sailors now advocate the use of a parachute sea anchor for heaving-to, which will bring the boat directly into the wind and stop it dead in the water.

It must be of sufficient diameter to completely stop the boat, otherwise the sea will be flowing past the rudder the 'wrong' way, and serious damage is likely to occur.

Often known as para-anchors, they're derived from circular aerial parachutes, and are deployed from the bow on a long rode.

The rode is chain-to-nylon rope, but reversed so that the chain is at the bow end.

Rigged thus, chafe in the bow roller won't be an issue, and the para-anchor will remain submerged.

It's a totally passive device; once it's deployed the crew may well opt to go below and sit out the storm.

Parachute Sea Anchor Issues: Your Questions Answered

Drogues

Running before a full gale on the edge of control may be acceptable for a fully-crewed racing yacht, but not so for the likes of us sailboat cruising types. The risks are enormous; falling off a crest into the trough may cause huge damage to the hull, and the prospect of being hurled end-over-end - pitchpoling - is almost unthinkable.

The sailboat must be slowed down to a manageable speed of 6 knots or less. Traditionally this was done by towing warps astern to create drag and keep the boat stern-on to the seas. There are a number of purpose-made drogues of various designs on the market, which when properly deployed have a more predictable and consistent speed-limiting affect than warps.

They fall into two basic categories - medium-pull and low-pull devices.

Medium-Pull or Series Drogues

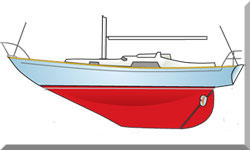

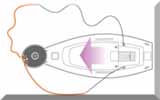

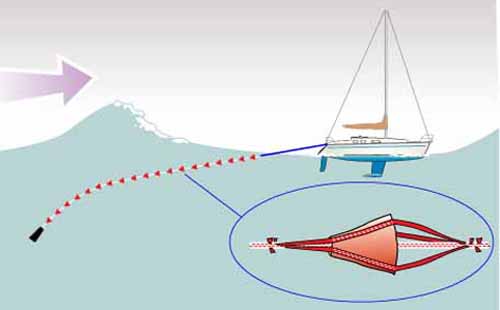

Drogues are always deployed from the stern - never the bow.

Drogues are always deployed from the stern - never the bow.Probably the best known of the medium-pull types is the series drogue, designed by the late Donald Jordan. As its name suggests, this is a string of a hundred or more cone-shaped drogues tied at intervals along a length of nylon rode.

One of these, providing it's correctly sized for the boat, will reduce boat speed to around one knot or so. Not enough to provide steerage way, so as with the parachute sea anchor, you may wish to go below and sit it out.

Low-Pull Drogues

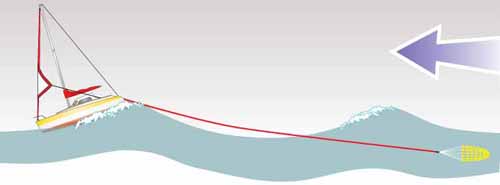

The drogue must be positioned such that it remains below the surface at all times.

The drogue must be positioned such that it remains below the surface at all times.These will slow down the boat to a much lesser extent - typically limiting boat speed to around 4 to 6 knots, which enables the helmsman to steer the boat, at least to a degree.

One of the benefits of the low-pull drogue is that it can be used effectively in situations other than extreme conditions.

For example a speed-limiting drogue can turn a roller-coaster downwind ride into an easy, subdued sail without adding much to your passage time, as would a medium-pull device - just the thing in boisterous trades when sleeping is next to impossible.

A speed limiting drogue will usually be constructed of heavy canvas and/or webbing, and is deployed on either a bridle or - if increased steering ability is required - from the quarter on a single rode.

A great deal of research has gone into the design of drogues of this type, much of it developed from the design of devices used to slow down space re-entry capsules and bringing expensive jet fighters to a stop before they reach the end of the runway.

Consequently you shouldn't be tempted to make one yourself - the odds are it will let you down when it really matters.

Sailing Drogue Issues: Your Questions Answered...

Recent Articles

-

Gozzard Sailboats: Timeless Cruisers for Liveaboard & Offshore Sailing

Jul 01, 25 03:42 PM

Explore Gozzard sailboats: their heritage, robust construction, and comfortable liveaboard design. Discover why these classic cruising yachts are built to last. -

Feeling Sailboats: Your Guide to Models, History & Cruising

Jul 01, 25 01:15 PM

Explore the enduring appeal of Feeling sailboats! Discover Kirie's innovative designs, famous models like the Feeling 850 & 446, lifting keels, interior comfort, and what to consider when buying a use… -

Etap Sailboats: Unsinkable Design & Comfort for Cruising

Jul 01, 25 02:44 AM

Discover the legacy of Etap sailboats, renowned for their unsinkable double-hull construction, robust build, and comfortable interiors. Explore popular models like the Etap 22, 28i, 32i & 38i.