- Home

- Cruising Boats

- Self Steering Gear

Windvane Self Steering Gear

for Sailboats

Not so long ago you could tell offshore sailboats from their coastal cousins by the windvane self steering gear bolted to their transoms, but this is no longer true. These days, many offshore sailors now opt for a compact and discreet electronic steering system instead.

As a big fan of windvane self-steering gears, I think that those sailors who rely entirely on power hungry - and often unreliable - electronic steering systems may be missing a trick.

If there's enough wind to sail, a vane gear will steer the boat for hour after hour without anything other than the occasional minor course adjustment by the helmsman.

And being entirely wind driven, there's no drawdown on those precious amps residing in your battery bank.

Under power though, the windvane self steering gear just won't behave at all - and that's where electronic steering systems come into their own.

Ideally, an offshore sailboat will be fitted with both systems; the windvane self steering gear for sailing and the autopilot for when under engine power. But how do they compare?

Windvane Self Steering Gear and Electronic Autopilots Compared

Windvane Self Steering Gear

|

Electronic Autopilots

|

How Do Windvane Self Steering Gears Work?

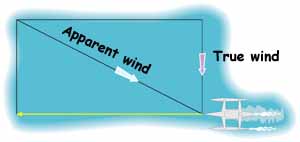

Essentially, these entirely mechanical devices sense the apparent wind direction and steer the boat on a course relative to it.

The apparent wind, a concept familiar to all sailors, is the wind we feel when standing on deck.

Only if the boat is stationary will the true wind be the same as the apparent wind.

Sensing The Apparent Wind

For a brief refresher, let's imagine a stationary boat with a ten knot wind on the beam...

As the boat moves ahead the apparent wind will move forward of the beam and increase in strength.

A further increase in boat speed will bring the wind further ahead and increase its apparent speed.

These changes will be sensed by the masthead wind direction indicator, which will align with the apparent wind - and the windvane will react in exactly the same manner.

The wind you feel...

The wind you feel...To carry this scenario to the extreme, if the vessel was a racing trimaran creaming along at 20 knots then it would effectively be close-hauled although still sailing on a beam reach.

So the factors affecting apparent wind are:~

- True wind speed,and

- True wind direction, and

- Boat's course relative to the true wind direction, and

- Boat's speed over the ground.

And the wind is never constant. It gusts, veers and backs, each of which will cause a change in apparent wind, to which the windvane reacts with a course change.

But as the sails are trimmed to the relative wind, the boat continues to sail efficiently, the heading being continually adjusted as if by an expert helmsman.

When the actual course deviates from the desired course to the extent that it's necessary to do something about it, then a gentle tweak of the course adjustment line and some sail trimming gets everything, well, back on course.

So how do windvane self-steering gears work? Put simply, the windvane senses the apparent wind then through a linkage to either the boat's own rudder or a separate auxiliary rudder, adjusts the sailboat's course relative to the apparent wind.

1 ~ The Windvane

The steering impulse is generated by the apparent wind flowing across the surface of the windvane. The simplest windvanes are made of marine ply, so it's easy to produce a few spares - but it's important that these are cut to the same shape as the manufacturer's design, and absolutely vital that they're within prescribed weight tolerances.

Other materials used are plastic, aluminium and synthetic fabric stretched over a metal frame.

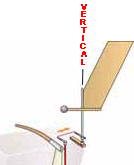

There are two types of windvane: those that pivot around a vertical axis, and those that pivot around a horizontal axis.

Vertical Axis Wind Vanes

Vertical axis self steering gear

Vertical axis self steering gearVertical axis windvanes rotate about their leading edge, much like a weathercock, and always point directly into the wind. Consequently, the vane area responding to the action of the wind is relatively small.

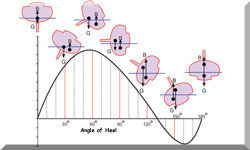

A counterbalance is fixed ahead of the axis to prevent gravity deflecting the windvane when the boat heels. When the boat wanders off course the windvane is deflected by the same angle as the off-course deviation.

The corrective steering energy generated by this deflection is small, owing to the negligible torque generated by vertical axis windvanes.

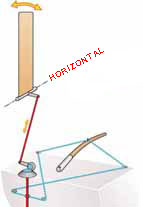

Horizontal Axis Wind Vanes

Horizontal axis self steering gear

Horizontal axis self steering gearHorizontal axis windvanes rotate about their lower edge, and are counterbalanced such that, in a no-wind condition or when facing edge-on directly into the wind, they will stand upright until deflected from that condition.

When the boat wanders off course and the wind strikes the windvane from one side, it tilts over exposing the whole of one face to the force of the wind. As a result it has a substantially larger effective area that the vertical axis windvanes.

Horizontal axis windvanes are therefore able to exert considerably more leverage than vertical axis windvanes and are said to be over five times as efficient.

In practice, the axes of such vanes aren't horizontal but are inclined at an angle of about 20°. This is to counteract the characteristic of truly horizontal vanes to slam hard over from side to side producing a correspondingly dramatic effect on the steering. By inclining the axis, the vane's power diminishes as it's pushed over producing a much more sensitive steering effect.

2 ~ The Linkage

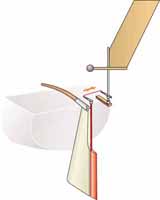

Auto-Helm cable-operated self-steering gear

Auto-Helm cable-operated self-steering gearThere are several ways of transmitting the steering impulse from the windvane to the rudder. They include bevel gears, pushrods and sheathed push-pull cables. This latter method allows the windvane to be positioned to avoid dinghy davits and the like, which may otherwise preclude the use of a vane-gear system. The Auto-Helm is an example of the cable operated type.

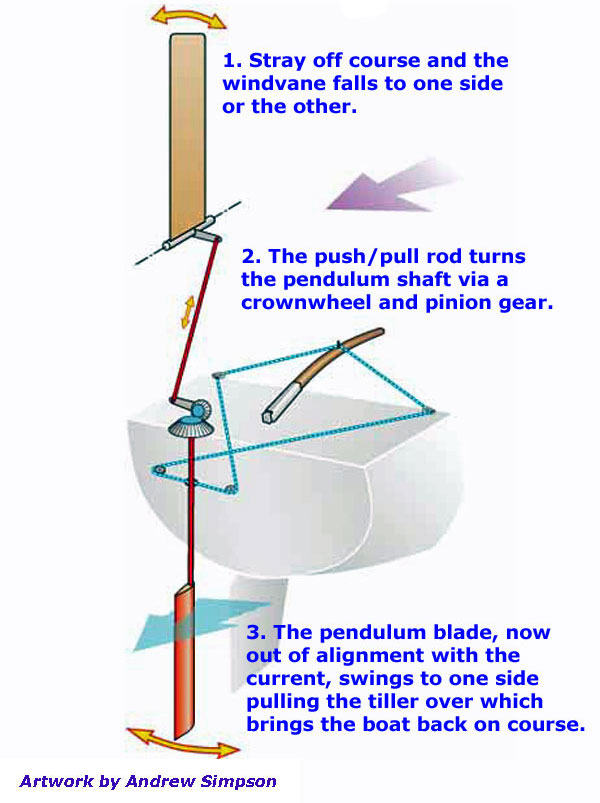

Apart from direct action windvane self steering gears where the vane operates its own rudder, most gears use some form of servo effect.

Perhaps the simplest example is where a trim tab (in effect a relatively tiny rudder) is fitted to the main rudder blade. The windvane alters the angle of tab and the water flow acting upon it pushes the rudder blade to one side. It could be said that the tab steers the rudder and the rudder steers the boat.

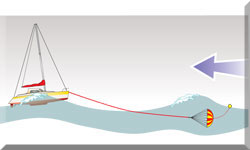

Much more powerful are what are known as 'servo-pendulum' windvane self-steering gears. On these, the windvane turns a high aspect ratio blade which is swept to one side or other by the water flow. At any sort of speed, the power generated by this action is awesome. Its action is harnessed by steering lines which are led back to the tiller or wheel.

Most gears employ one or other of these servo mechanisms, sometimes even combining the two in the same unit.

NEW!

Just published, Andrew Simpson's eBook that contains everything you need to know about Windvane Self-Steering Gears.

If you're thinking about buying one of these wonderful devices, you really should take a look at this ebook before deciding on a model that may not be the best for your boat.

Considering its true value, you'll be absolutely amazed at its price! In a nice way, of course...

Take a look at 'Secrets of Windvane Self-Steering' Here!

Feedback

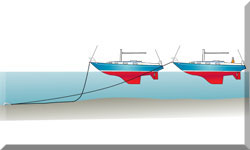

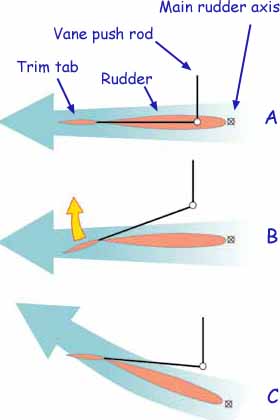

Trim tab acting on the boat's rudder

Trim tab acting on the boat's rudderEarly windvane self steering gears - particularly the super powerful pendulum servo gears - could be quite violent in their actions and it became necessary to dampen their excesses by introducing some form of corrective feedback into the linkage geometry.

There are various ways of achieving this but an easily understood example can be demonstrated by looking at a simple trim tab gear as shown here.

By having the trim tab arm pivot behind the rudder's axis, the action of the tab gradually reduces to becomes zero as the rudder blade turns.

With the boat on course (A) the trim tab has a neutral effect but any deviation from the course (B) is sensed by the windvane which applies corrective action.

Because the trim tab's control point is astern of the rudder's axis (C), as the rudder swings over it progressively negates the the trim tab's effect.

Types of Windvane Self Steering Gears

Direct Action with Auxiliary Rudder

These are self contained units where the vane directly operates its own rudder with no servo effects being employed. The Hydrovane is by far the best known of this type.

Servo Tab on Main Rudder

Vertcal axis vane gear operating a trim tab on the rudder

Vertcal axis vane gear operating a trim tab on the rudderOne of the oldest and simplest forms of self-steering and probably the least sensitive.

It should be noted that the action of the tab first steers the boat the 'wrong' way - that's to say, its immediate effect before the rudder turns is to further promote the yaw.

This arrangement is shown in the sketch on the right.

Servo Tab on Auxiliary Rudder

Another self-contained arrangement. The main rudder is usually trimmed then lashed to compensate for any helm bias, leaving the self-steering gear to correct minor course deviations.

One drawback with this arrangement is that the auxiliary rudder is relatively small and may not be sufficiently powerful to bring the boat back from being violently thrown off course.

Servo Pendulum on Auxiliary Rudder

Here a servo blade operates its own rudder, dispensing with the need for steering lines. It shares the limitations of the previous type, with the notable exception that the pendulum blade contributes to the steering effect.

Servo Pendulum Acting on Main Rudder

Horizontal axis servo-pendulum

windvane self-steering gear

Horizontal axis servo-pendulum

windvane self-steering gearFar and away the most powerful type of windvane self-steering gears.

However, the steering lines must be led to the tiller or wheel, which can be awkward on centre cockpit boats.

Since it's the main rudder that actually does the steering, it doesn't suffer the shortcomings of auxiliary rudder types.

The Monitor and the Aries windvane self steering gears are the best known vane gears of this type.

Servo Pendulum and Auxiliary Rudder self-Steering Gear Types Compared...

Servo Pendulum Types

|

Auxiliary Rudder Types

|

My preference? A servo pendulum system like the Monitor, or an Aries windvane self steering gear, does it for me.

Recent Articles

-

Albin Ballad Sailboat: Specs, Design, & Sailing Characteristics

Jul 09, 25 05:03 PM

Explore the Albin Ballad 30: detailed specs, design, sailing characteristics, and why this Swedish classic is a popular cruiser-racer. -

The Hinckley 48 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:44 PM

Sailing characteristics & performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley 48 sailboat... -

The Hinckley Souwester 42 Sailboat

Jul 09, 25 02:05 PM

Sailing characteristics and performance predictions, pics, specifications, dimensions and those all-important design ratios for the Hinckley Souwester 42 sailboat...