- Home

- Offshore Seamanship and Heavy Weather Tactics

- Transatlantic Passage

Transatlantic Passage: The Reality of Sailing the Ocean

In a Nutshell...

Our 3,000 nautical mile crossing was a tremendous success, completed with no breakages aboard Alacazam. The voyage, which took just under three weeks, confirmed the strength of the vessel and the reliability of our equipment, particularly the Aries windvane self-steering. The average daily run was 150.3 miles, falling somewhat short of the 200-mile aspiration due to consciously undersailing the boat to manage the confused cross seas and limit rolling. The main lessons learned centred on optimising the downwind rig with identical twin headsails and the crucial importance of correctly positioning solar panels to avoid power-sapping shadows.

The Departure Point, Marina del Atlantico, Tenerife

The Departure Point, Marina del Atlantico, TenerifeTable of Contents

This article details the real-world experiences and practical considerations of our transatlantic passage. It serves as a case study in Mastering Offshore Seamanship by covering everything from essential boat design and rigging decisions to the reality of watchkeeping and provisioning over 3,000 miles. As an experienced offshore sailor, you will appreciate the technical details and lessons learned about preparing a vessel like Alacazam for the ocean and the strategies employed during the crossing.

Planning & Preparation: Route, Boat & Crew

Whilst the prospect of sailing the ocean was not new to Mary and me—having cruised the offshore waters of the UK, France, Spain, Portugal and the Mediterranean—an ocean crossing definitely was.

But it had to be done. After all, we had recently completed the construction of Alacazam, a lightish displacement cruising boat specifically designed for ocean sailing and living aboard. So, with gainful employment abandoned and house rented to a tenant, it was finally time to go. North or South?

The decision was easy; it was south for us. Palm trees and tradewinds beat icebergs and Arctic blizzards every time.

We departed on 6th July 2001, cruising south from Plymouth via France, Spain, Portugal, Madeira and the Canary Islands. December 2001 found us holed up in Marina del Atlantico, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, waiting for the tradewinds to establish themselves before setting off across 3,000 odd miles of Atlantic Ocean on the well-trodden path of the so-called 'Milk Run'.

Alacazam: Design & Performance Metrics

Alacazam's composite construction is a marriage of traditional materials and modern technology. Her hull is built of Western Red Cedar using the wood epoxy technique; the doghouse and cockpit are GRP mouldings. The fin keel is a lead-filled GRP moulding letter-boxed through the hull and bonded solidly in place, with a lead bulb bonded to its base. The partially balanced rudder is hung on a half skeg similarly letterboxed and bonded into the hull structure.

The prop shaft, supported by an 'A' bracket rather than the less robust 'P' bracket, spins a two-bladed folding propeller. The whole vessel, comprising hull, bulkheads and internal structures, is an immensely strong monocoque.

Here's the story of her build...

Alacazam

AlacazamHer vital statistics are:

| Characteristic | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Length overall | 11.5m (37.5 feet) |

| Waterline length | 10.6m (34.5 feet) |

| Beam | 3.9m (12.5 feet) |

| Draft | 2.2m (7 feet) |

| Displacement | 7,023kg (7.75 tons) |

| Displacement/length ratio | 159 |

| Sail area/displacement ratio | 18.28 |

Expected Passage Time

Alacazam's waterline length of 10.6m gives her a theoretical maximum displacement hull speed of 8.2 knots, equating to just under 200nm a day. We had experienced 12.5 knots under a full genoa and reefed main whilst reaching in a force 6, so we knew she could go faster than hull speed in the right conditions.

We aspired to an average of 150nm per day, meaning the 3,000 nautical mile passage would take around 20 days.With such aspirations, we departed Marina del Atlantico, Santa Cruz de Tenerife on 13th January 2002, bound for the West Indies.

Downwind Sailing Rig & Tactics

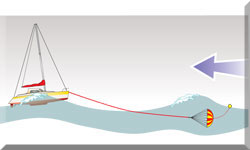

We began on a broad reach with full main and genoa set, eventually changing to poled out main with preventer, and genoa poled out to windward. This 'Wing-and-Wing' rig was fast and not too rolly, but it was not relaxing. If the wind pipes up and a reef in the main is necessary, the yacht has to be turned to windward and the sails adjusted, which is too much work in a big sea.

'Wing & Wing' Rig

'Wing & Wing' RigAlthough not shown here, we did have a preventer on the main

Consequently, I was very pleased to get into the trade winds proper where I could get the main down and set twin headsails.

The Twin Headsail Setup

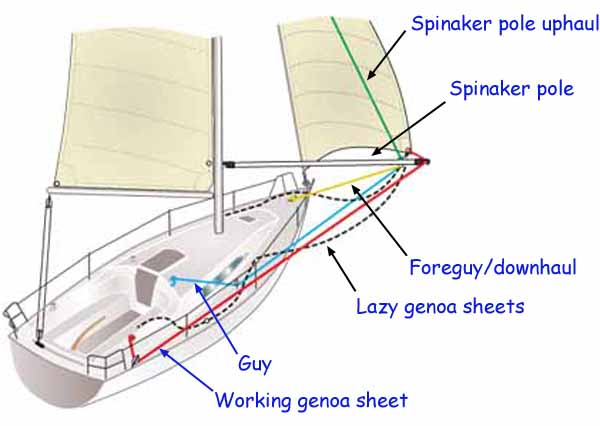

I hoisted the yankee up the second luff groove of the furling gear, leaving the genoa set in the other groove. The sails were controlled by:

- The lazy genoa sheet reeved through a block on the end of the pole.

- The lazy sheet from the yankee reeved through a block at the end of the boom, which was squared off and held in place by the mainsheet, topping lift, kicker, and preventer.

Eased together, this allowed both headsails to be rolled around the Furlex gear using the furling line. It worked perfectly as a throttle from a mechanical point of view.

A Lesson Learned

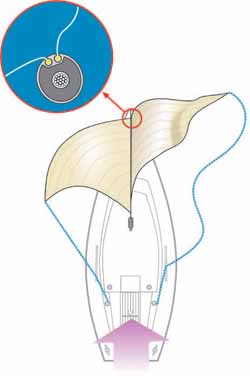

Hoisting the yankee up the second luff groove while barrelling downwind in big seas proved difficult, with high friction caused by the sail blowing forward against the foil. Only sometime later did the obvious method dawn on me: if I had gybed first, poling the genoa out to port, the port luff grove would have been facing forward, downwind. This would have minimised friction. Another lesson learned; I will know next time.

Hoisting twin headsails the easy way...

Hoisting twin headsails the easy way...The primary problem with the twin headsails was that the sails differed too much in both size and shape, creating an unbalanced rig as the sail area was reduced. This did little to help the appalling rolling. A second identical genoa set in place of the yankee would have been perfect, and would be the only change I would make to Alacazam's long-distance downwind rig.

Atlantic Crossing Strategy & Weather

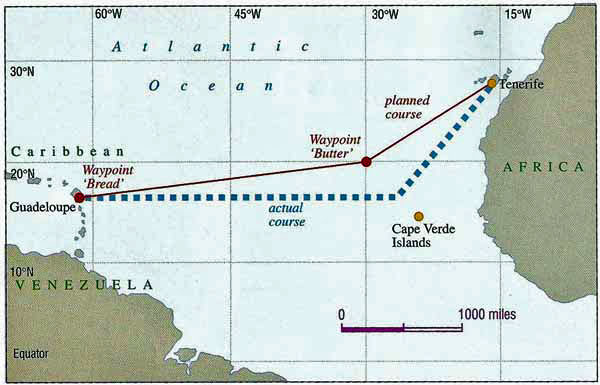

Traditionally, the advice is to sail south until the butter melts and then turn right. Modern thinking suggests 25ºN, 25ºW as being the point at which the tradewinds become properly established. After intense daily study of the on-line weather predictions, we programmed the GPS with waypoint "BUTTER" at 20ºN, 30ºW, our 'turn right' point.

In the event, we sailed considerably further south than this, so much so that a stop in the Cape Verde Islands was considered. Then the tradewinds filled in and we rolled our way westwards, Cape Verde's abandoned till next time.

The 'Bread & Butter' route across the Atlantic Ocean

The 'Bread & Butter' route across the Atlantic OceanWeather Information at Sea

Our attempt to use a TARGET SSB Receiver and Weatherfax software with our new state-of-the art laptop was defeated by the incompatible operating systems (DOS software versus Microsoft Windows 2000ME). We were also reluctant to risk our expensive laptop in the rolly conditions.

We ultimately relied on:

- NAVTEX from the Las Palmas station for the first few days.

- Eavesdropping SSB conversations on Herb's Net (12359kHz at 2000 Zulu) and Trudi in Barbados (21400kHz at 1300 Zulu, providing an English translation of the French forecast).

However, as a friend's experience demonstrated, knowing what is coming does not always mean you can do much about it. You might just as well forget about weather until it arrives and deal with it then.

Sea Conditions & Squalls

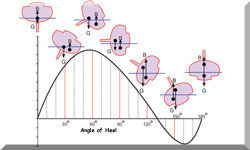

We expected Beaufort force 4 to 5 north easterlies, but the wind seldom blew less than a 5 and was frequently considerably higher. The sea conditions came as something of a surprise. Frequently we had a 4m to 5m wave system from the east coupled with a large ocean swell from the north. When the wind increased to 30 knots or more, these cross seas became more confused than you would ever believe.

Squalls were frequent. We were delighted to find that the squalls were very visible on Alacazam's newly installed Radar, and by tracking them from 12 miles or so, most could be avoided without difficulty.

Self-Steering, Navigation & Watch Systems

Helming & Steering

We relied upon 'Arry', our ancient Aries vane gear bought second-hand for £150. Helen Franklin, daughter of the designer Nick Franklin, overhauled it to as-good-as-new condition. I had been concerned whether it would work in downwind conditions, but it performed extremely well. I would not contemplate a long-distance cruise without windvane self-steering, preferably of the servo-pendulum type.

On the few days when there was insufficient apparent wind over the blade, we resorted to our 20-year-old Autohelm 2000. Despite my lack of confidence in its vintage and maintenance, it stood up to the loads caused by the large cross seas.

Navigation Redundancy

Off Portugal, the active antenna of our Magellan 5200DX GPS expired, forcing us to rely on dead reckoning and the sextant. To our great relief, Porto Santo showed up exactly where it was supposed to. Not wishing to put ourselves to the test again, we bought a handheld Magellan 315 in Madeira and a fixed Garmin 320 in Tenerife. Nothing like a bit of system redundancy. With waypoint 'BREAD' off Guadeloupe programmed into the Garmin, navigation was simplicity itself.

Watchkeeping Rota

We saw two ships on the crossing, both during the hours of darkness, and one of them would have come very close (at best) to running us down if we had not been keeping watch. We kept strictly to the following watch system:

| Time | Watchkeeper A | Watchkeeper B | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0800 to 1400 | ✔ | 6 hrs | |

| 1400 to 2000 | ✔ | 6 hrs | |

| 2000 to 2400 | ✔ | 4 hrs | |

| 0000 to 0400 | ✔ | 4 hrs | |

| 0400 to 0800 | ✔ | 4 hrs |

This system ensures that we each did the two night watches on alternate nights and had a 6-hour daylight watch every day, which seems fair. 'Leap hours' had to be applied at every 15 degree increase in longitude to keep the hours of daylight and darkness in the right place.

But there are other watch systems for a crew of two...

Power Generation: Solar, Wind & Engine

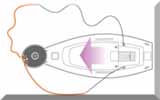

Alacazam had no electrical luxuries, needing only about 120 amp hours a day to keep things ticking over. Two 140Ah house batteries provided this power and were charged by a combination of two 50 watt Solarex solar panels, a Rutland 910 wind generator, and a 65A alternator on the engine.

The downwind, rolly conditions were not good news for the wind generator, which contributed probably no more than 60Ah per day. The solar panels contributed a further 35 amp hours, leaving a deficit of about 25Ah, which was made up by running the engine for about an hour each day.

Solar Panel Placement Error

The solar panels would have performed much better, perhaps avoiding the need to run the engine at all, had I not done something particularly crass before leaving Plymouth. I had mounted the radar scanner, the radar reflector, the wind generator, and various aerials above the solar panels.

All these components conspired to throw shadows across the panels. I had also mounted the panels on a ply base, which reduced ventilation, further affecting performance. The plan now is to move the wind generator, radar scanner and reflector further outboard, resite the other stuff, and dispense with the ply base to give the solar panels a chance to perform to their optimum.

Provisioning & Galley Management

Mary did most of the cooking, in return for which I did most of the dish washing. We fully provisioned in England and topped up on our passage south, buying further quantities of tinned and packaged food in Tenerife where it was cheaper than in the West Indies. We simply filled all the available lockers with food.

Food Storage

Fresh fruit and vegetables were stored in net hammocks in the forepeak. These must be sited such that it is impossible for adjacent hammocks to crash into each other or the hull sides, which resulted in 'mortal injuries' to a number of our tomatoes and avocado pears when the string broke.

Alacazam's galley surfaces are properly fiddled which prevents things falling off, but does nothing to prevent things sliding about. Enter non-skid tablemats! In our view, they are right up there with 'Arry' the Aries as essential cruising gear.

Fruit & Veg stowage

Fruit & Veg stowageWeevil Infestation

One day, we noticed a small black bug, then a few more, then a lot more. We had an infestation of weevils traced back to several packets of rice purchased in Spain. They had invaded packets of pasta, cornflour and breakfast cereals. The contaminated food went over the side, and the boat was liberally doused with insect repellent. The whole process took us an exhausting day.

Catch of the Day

Our diet was enhanced by the occasional dorado (also known as the mahé mahé, or dolphin fish), which fell to my lure trailed astern on a trolling line. Flying fish found on deck were scaled, gutted, opened up and grilled whole—delicious!

Apart from a Brown Booby (we called him 'Bird') that hitched a ride with us for 11 days, the only seabirds we saw were tropic birds and petrels. We also had a False Killer Whale circling the boat for two hours one day.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Here's Mary's in-depth 'warts and all'" account of the crossing, where most of the warts appear to be mine. Funny, that...

Here's Mary's in-depth 'warts and all'" account of the crossing, where most of the warts appear to be mine. Funny, that...Frequently Asked Questions

What was the biggest challenge of the passage?

What was the biggest challenge of the passage?

The most challenging aspect was managing the confused cross seas that arose when the 4m to 5m wave system from the east coupled with a large ocean swell from the north. These conditions made the rolling intense, which required us to reduce sail and meant that the planned 200-mile day was sacrificed for comfort and self-preservation.

Did you use the Autohelm or the Aries more for steering?

Did you use the Autohelm or the Aries more for steering?

The Aries windvane self-steering gear ('Arry') was our primary and preferred means of steering. It performed extremely well, even in the demanding downwind conditions. We only resorted to the 20-year-old Autohelm 2000 on the few days when there was insufficient apparent wind to keep the Aries blade in equilibrium.

What single change would you make to the downwind rig?

What single change would you make to the downwind rig?

I would replace the mismatched yankee with a second, identical genoa (or headsail of similar size and cut) to be set alongside the primary genoa. This would create a balanced twin headsail rig that could be efficiently reduced in area using the furling gear without creating undue balance problems and exacerbating the rolling.

How did you manage to avoid the squalls?

How did you manage to avoid the squalls?

We used Alacazam's newly installed Radar to track the squalls. They were very visible on the screen, and by observing their course from 12 miles or so out, we were able to adjust our heading slightly to avoid most of them without difficulty.

How long did the actual transatlantic crossing take?

How long did the actual transatlantic crossing take?

We departed Santa Cruz de Tenerife on 13th January 2002. Our best noon-to-noon run was 177 miles, and our average daily run was 150.3 miles. The total time for the 3,000 nautical mile crossing was just under three weeks.

Recent Articles

-

Modern Boat Electronics and the Latest Marine Instruments

Dec 20, 25 05:27 PM

Should sailboat instruments be linked to the latest boat electronics as a fully integrated system, or is it best to leave them as independent units? -

Hans Christian 43: Classic Bluewater Cruiser & Liveaboard Sailboat

Dec 10, 25 04:37 AM

Explore the Hans Christian 43: a legendary heavy-displacement, long-keel sailboat. Read our in-depth review of its specs, design ratios, and suitability for offshore cruising and living aboard. -

Planning Your Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle: An Ocean Sailor's Guide

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Seasoned sailors share their methodical risk analysis for planning a secure Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle, covering financial, property, and relationship risks.