- Home

- Offshore Sailing

- Sailboat Flag Etiquette

- Tradewinds Sailing

Tradewinds Sailing Tips

Tradewinds sailing, the stuff of dreams for most offshore cruising sailors. Blue skies, fluffy white clouds, a deep blue sea and long gentle ocean swells. The warm breeze over the transom keeps the boat bowling along nicely and the miles reel off towards your exotic, tropical destination.

Well it can be like that, but often conditions are considerably more boisterous and with the wind directly astern the boat will be rolling. Rolling rather a lot probably.

With a roll period of say six seconds, she'll roll 10 times a minute, or 600 times an hour, or 14,400 times a day, or around 300,000 times on the classic tradewind passage from the Canary Islands to the West Indies.

Line squalls will bowl in from astern, often accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds. Goose-winging with a poled-out jib and a main secured by a preventer, rounding up into the wind to put a reef in will be no fun at all.

Life will be more agreeable all round with the mainsail stowed away and twin headsail rig set - and a twin-luff groove headsail furling gear lends itself very nicely to this rig.

A Twin Headsail Rig for Tradewinds Sailing

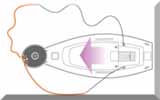

Most of us cruising types have twin luff groove headsail furling systems on our sailboats, which are ideal for tradewind sailing. But rather than hoisting two headsails at the same time, each in their respective luff groove, a better approach is to attach a good quality block to the head shackle on the top swivel and reeve a 6mm Spectra halyard through it with both ends tied off to the tack swivel on the furling drum.

The usual headsail can be hoisted and operated in the normal way and the second headsail hoisted only when needed.

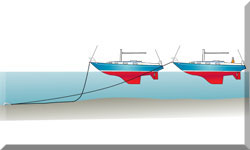

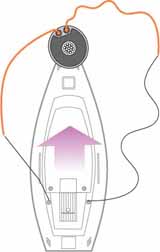

Rigging twin headsails on twin luff foil.

Rigging twin headsails on twin luff foil.When hoisting the second headsail, make sure that the luff groove is facing forward - if it isn't, a gybe will ensure that it is. If you try to hoist the sail with the groove facing aft, the wind will blow the sail around the foil and the resulting friction will be such that you won't be able to hoist the sail.

With two headsails set in this way, they can be furled simultaneously if a squall comes through.

In the absence of a spare luff groove, the second headsail can be set flying, but this is likely to induce more rolling than the twin-luff set-up. Either way, the twin headsails will be more stable if they are of similar size and supported by similar length poles.

Without a second pole, the boom can be squared off and the jib sheet passed through a block on its end. This though, is a poor substitute.

Self Steering on a Tradewinds Sailing Passage

You won't want to helm across several thousand nautical mile of ocean. You'll need some form of self steering to take you across...

Windvane Self Steering

Windvane self steering gears only work well if there's a decent flow of air over the vane. On a tradewind passage, the wind is likely to be pretty much dead astern, so the apparent wind speed will be less than the true wind speed.

For example, if you're bowing along at six knots with a 12 knot breeze blowing directly over the transom, the windvane gear will only feel a 6 knot wind over its vane. This is at the very limit of most windvane gears' performance, so you shouldn't rely too heavily upon them for your self-steering requirements on a tradewinds sailing passage.

Electronic Autopilot

Most skippers will choose this electronic steering system, perhaps as a back-up for the windvane gear or as their primary self-steering system. But it requires electrical energy to drive it, often quite a lot of it - which has to come from somewhere.

Sheet-to-Tiller Steering for Downwind Tradewinds Sailing

The main requirement for this approach is a tiller, which is becoming increasingly rare on modern yachts, as fashion demands that wheels are the thing to have now. OK, if you've got a centre-cockpit sailboat then you've little choice in the matter, but many aft-cockpit sailboats would be better off with tillers in my view. But don't get me started on the tiller versus wheel issue...

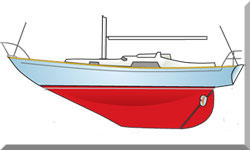

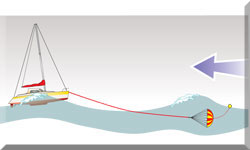

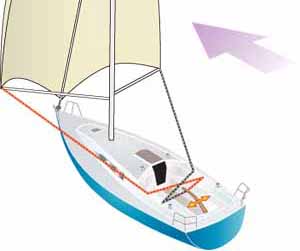

The sheet-to-tiller self steering with twin headsail tradewind rig.

The sheet-to-tiller self steering with twin headsail tradewind rig.So let's assume that, like me, you've got an aft-cockpit sailboat with a tiller. With the twin headsail tradewind rig set, cross over the sheets in the cockpit through a pair of blocks and tie them off to the tiller.

There'll be a fair amount of fiddling around with the position at which you tie them off to get the balance right, particularly if your headsails are not quite the same shape and size.

This is done with the tiller between your legs, one eye on the compass, the other on the windex and a headsail sheet in each hand. An interesting experience for single-handers, but once set up this rig will take you downwind with little further tweaking. Don't forget that if the wind changes direction, so will your course.

Few of us would set out on a tradewinds sailing passage relying solely on sheet-to-tiller steering, but when all else fails.....

Artwork by Andrew Simpson

Keeping the Batteries Charged on a Tradewinds Sailing Passage

Larger cruising sailboats are likely to have a built-in generator to provide a reliable charge to their batteries when they need it, but without one of these you'll need to find some other way of charging your batteries. Yes, you can run the engine for a couple of hours each day to charge the batteries, but who wants to do that unless you have too?

Wind Chargers

Much like the windvane self-steering gear, the windcharger's performance is a function of the strength of the apparent wind. The stronger the apparent wind the faster the blades will spin, and the higher the speed of rotation the more of those precious little amps will be deposited into the battery bank.

So you'd be wise not to expect too much from your wind generator on a tradewinds sailing ocean passage.

Solar Panels

Being in the tropics, as that's where you'll find the tradewinds, there'll be lots of sun high in the sky. Perfect for solar panels; they'll perform at their best. But in the tropics the nights are long, when solar panels don't perform at all.

Towed Generators

These really kick out the battery juice at any time of the day or night, providing you've got reasonable boat speed through the water. However much of it you've got though, a towed generator will reduce it by up to half a knot, or at a cost of up to 12 nautical miles a day.

Large fish have been known to consider towed generators as part of their diet.

And if the rotating line of your towed generator cosies up to your trolling line, the resultant tangle will stay in your mind for a long time...

Shaft Generators

As their name suggests, these are driven by your engine's propeller shaft. Under sail, and with the engine turned off and in neutral, the normal function of the propeller is reversed. Now the water flowing through it turns it and the shaft, thus driving the prop shaft generator.

They generate a useful charge for the batteries, but a propeller turning freely with the engine off creates a lot of drag. More so than a towed generator, so you can expect a significant reduction in boat speed.

Many of us have installed either a folding or a feathering propeller to reduce drag to a minimum when the engine's not in use - in which case a prop shaft generator wouldn't work at all.

And Finally...

So far we've considered tradewinds sailing as a downwind ocean passage, such as the tradewind route across the Atlantic from the Canary islands to the Caribbean.

Arriving at your destination, you'll find the delightful islands of the West Indies spread out in an arc across the easterly tradewinds.

Now your tradewinds sailing will not be a downwind sleigh ride as on the Atlantic Crossing, but will usually be anything from a close reach to a broad reach, and fantastic sailing it is too.

Enjoy, you've earned it!

Next: The Classic Tradewinds Sailing Passage to the Caribbean...

Recent Articles

-

Small Boat Radar Systems: Your Questions Answered

Apr 13, 25 06:40 AM

Whatever your question about small boat radar systems, you're very likely to find the answers here... -

How a Marine EPIRB Can Get You into Trouble, As Well As Out Of It

Apr 12, 25 05:51 PM

Activating a marine EPIRB or a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) when you're not in distress can get you in big trouble with the Coastguard, as this cautionary tale relates. -

What is an EPIRB?

Apr 12, 25 05:43 PM

Got any EPIRB-related questions? You're almost certain to find the answers here...