- Home

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Sailboat Keels

Sailboat Keels - Deep Fin Performance or Shoal Draft Convenience?

While it's true that deep-fin sailboat keels are the most efficient of all in terms of windward ability, many anchorages will be opened up to those who opt for a shoal draft alternative, accepting the perceptible loss to windward sailing performance.

Another benefit with shoal draught sailboats is the increased security to be had when lying alongside a wall or laid-up ashore, saving the cost of a cradle.

Sailboat keels serve two purposes:

1. to provide ballast low down and

2. to provide lateral resistance to the wind force exerted on the sails

And like all things in the sailboat world, there are trade-offs to be made.

But just what are the alternatives? Let's take a look...

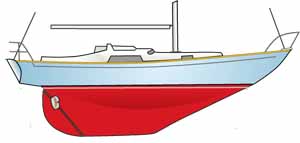

Long (or Full) Sailboat Keels

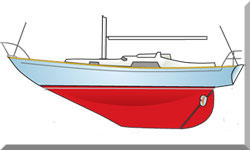

These sailboat keels are found on the heavy displacement boats of yesteryear, and are still popular with some long-distance cruising sailors. The Nicholson 32 sketched below is a popular example of a long keel sailboat.

Long Keel - Robust construction and a comfortable motion but inherently slow

Long Keel - Robust construction and a comfortable motion but inherently slowUnlike more modern keels they are built-in as part of the boat's hull construction which, together with encapsulated ballast, makes them extremely robust.

But although well-mannered under sail, such boats are slow and need a large spread of sail to get them moving, especially in light winds. This is largely due to the high wetted area, and consequent drag, of sailboat keels of this type.

In their favour though, long keel sailboats track through the water as if on rails, have a comfortable motion in a seaway and will heave-to readily.

The propeller is protected in an aperture and hulls of this type usually sail over floating fishing gear and pot buoys with impunity.

Close-quarters manoeuvring, such as wriggling in and out of a marina berth, is not their specialty.

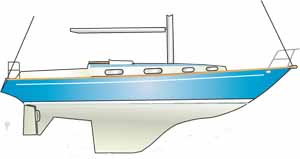

Encapsulated Fin Keels

Encapsulated Fin Keel - Most of the benefits of a long keel, but faster under sail and more maneuverable under power

Encapsulated Fin Keel - Most of the benefits of a long keel, but faster under sail and more maneuverable under powerThese were the natural development of long fin keels which, whilst retaining their positive attributes, greatly improved manoeuvrability due to the separation of the keel and the rudder.

The Contessa 32 sketched here is a highly regarded example of these long-fin and skeg-hung rudder sailboats.

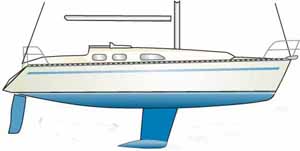

Deep Fin Keels

Deep fin keels are manufactured separately from the hull, and are subsequently bolted on. Keel bolts have a justified reputation as being 'suspect', owing to their habit of corroding undetected.

Deep Fin Keel - The racers choice, highly efficient and fast, but have been known to drop off because of poorly engineered fixings or corroded keel bolts

Deep Fin Keel - The racers choice, highly efficient and fast, but have been known to drop off because of poorly engineered fixings or corroded keel boltsBut this type of sailboat keel is more efficient to windward than the previous two keel types, creating more lift and reducing leeway.

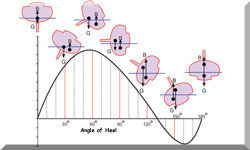

All sailboats make some leeway - perhaps just a few degrees - when sailing to windward, which creates an angle of attack between the fin keel and the water flowing past it.

Much like a sail, or indeed an aircraft's wing, this produces an area of low-pressure flow on one side of the foil and high pressure on the other. The keel tends to move into the low-pressure area, conveniently reducing leeway and dragging the boat up to windward.

Retractable Keels

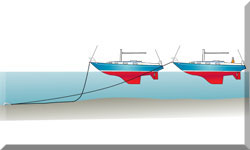

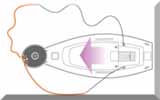

Retractable keel sailboats, or lifting keel sailboats, types rely on ropes and pulleys - or hydraulic rams in some cases - to retract a steel centreplate into a keel housing. Some types operate vertically and others pivot around a pin at the forward end, like that on the swing-keeler shown here.

Retractable Keel - Deep/shoal draught compromise that enables upright drying out, but subject to jams and mechanical failure

Retractable Keel - Deep/shoal draught compromise that enables upright drying out, but subject to jams and mechanical failureIn some designs a ballast stub keel is retained which contains the keel housing. Others have no stub keel at all and all of the keel housing projects into the boat to some degree, usually to the detriment of the accommodation.

When all goes well, sailboat keels of this type would seem the ideal solution to provide deep draft offshore and shoal draft when navigating in shallow waters.

Another much heralded benefit is the ability to dry out upright, particularly when partnered with a twin rudder design. Nevertheless, some offshore sailors may feel that that the added complexity and possibility of failure outweighs all other advantages.

Most skippers of lifting keel boats that I've spoken to have experienced, or continue to worry about, at least one of the following:

- That keel slot in the bottom of the boat. How well engineered is it to resist the side loads imposed on it by the centreplate?

- The rope and pulleys that operate the centreplate. When is something going to break?

- When are all the barnacles, firmly attached to the 'impossible to anti-foul' inner surfaces of the keel housing, going to gang-up and jam the centreplate?

- How soon before a stone wedges itself between the centreplate and the keel housing, firmly jamming it in the 'up' position?

- How much longer can I put up with the noise of the thing rattling around?

But they have their moments of glory...

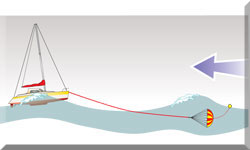

For UK yachtsman tempted by the prospect of warm water Mediterranean sailing, but not overly enthused about the exposed passage around the Iberian Peninsular and through the Straits of Gibraltar, a retractable keel sailboat will get him there through the Canal de Garonne and the Canal du Midi.

Twin, or bilge keels

These are a peculiarly British thing. Nowhere else do they seem to enjoy the same level of popularity.

Bilge (or Twin) Keels - Takes advantage of cheaper dryng moorings at the cost of performance under sail

Bilge (or Twin) Keels - Takes advantage of cheaper dryng moorings at the cost of performance under sailAlong with long-legged birds and wellie-clad bait diggers, bilge keelers are very much at home on tidal mud flats, where drying moorings are much less expensive than the deep water kind.

Apart from their shallow draft, the benefit of a bilge keeler is that these cheap moorings can be enjoyed without falling over - twice a day in fact.

And that's it, as far as I can see. Underway, their high wetted area and lack of low-down ballast can only detract from their sailing performance - and if you inadvertently run aground in one of these, you may be there for a while, since you can't heel the boat to reduce its draft.

But they're very popular here in the UK, so I mustn't be too rude about them.

Sailboat Keels with Bulbs or Wings

One way to reduce draft whilst minimising the affect on stability is to provide additional ballast in the form of a lead bulb on the bottom of the keel.

Bulb and Wing Keels - Low centre of gravity, good stability and reduced draught

Bulb and Wing Keels - Low centre of gravity, good stability and reduced draughtVariations on these types of sailboat keels include torpedoes, the Scheel keel and the wing keel.

Properly designed 'torpedoes' meet this requirement, and providing they don't project forward of the keel's leading edge - where they'll collect pick-up lines, discarded fishing nets and other assorted flotsam and jetsam - are a good solution for offshore yachts.

The Scheel keel, invented by the American designer Henry A Scheel, is said to create additional lift through the converse sections on top of the bulb, and appears on several highly-regarded offshore designs.

Wing keels develop this principle further, but share the same propensity for collecting unwanted hangers-on as the forward projecting torpedo.

Wings increase wetted area, and hence drag, but as well as producing more hydrodynamic lift they do provide a degree of 'damping' in a rolly anchorage.

You'll need to support the boat in slings to anti-foul the underside of the wing, or alternatively employ a diver to scrub it clean at regular intervals.

Tandem Keels

A Tandem Keel - this one is fitted to a Bavaria cruising boat.

A Tandem Keel - this one is fitted to a Bavaria cruising boat.This is a tandem keel, designed by Warwick Collins back in the 1980's. Essentially a tandem keel comprises two foils and a delta endplate to create a shoal draft keel which is genuinely as effective upwind as a deep keel.

These keels had some success on the racing circuit and were also found on cruising yachts, including Bavarias and Etaps.

At first glance it would seem that the water flow around the forward foil would disrupt the flow around the after one, but this is not the case. Owing to the boat's leeway, both keels operate in laminar flow.

Benefits of the tandem keel include:

- With 55%-60% of its weight in the endplate, stability is very good.

- The end plate dampens the boat's motion at sea, increasing crew comfort.

- The additional stability allows the rig to work more efficiently creating more drive and better boat speed.

- The tandem keels' lower aspect ratio (shallow and long) improves directional stability.

So what's not to like? Very little it would seem, although going aground with this (or any wing keel design) is likely to be embarrassing. And of course, they're expensive in comparison to less radical designs.

Next: Your Keel Questions Answered...

Recent Articles

-

How DSC Radio Greatly Improves Your Chance of Rescue at Sea

Apr 10, 25 03:03 AM

By far the most important feature of DSC radio is that it provides a safer way of placing a distress call to the coastguard, and now it can even be done with a handheld DSC/VHF radio -

DFC VHF Radio: Your Questions Answered

Apr 10, 25 02:57 AM

Got a question about the marine DFC VHF radio? Odds are, you'll find the answer here... -

How Does a Marine GPS Work?

Apr 09, 25 03:27 PM

You'll find the answer to 'How Does a Marine GPS Work?' and other GPS-related questions right here...